Saturday, October 28, 2006

Mets and Yanks: The Gonfalon Bubble

From "Play's the Thing," Woodstock Times, October 26, 2006:

With polo shirts and seersucker trousers stored in the attic for the next six months, it’s time to wrap up the baseball season too. The Cardinals and Tigers pecked and clawed at each other for five more desultory evenings, but when viewed through Gotham-colored glasses, the national pastime of 2006 had concluded some time before.

Laid away for winter storage, each memory is briefly savored or rued on the way to being forgotten. And with the Mets and Yankees it is the regret, not the joy, that lingers; long distant is the confidence of summer, when each had emerged as the best team in its league. While all but the credulous knew that a Subway Series was no certainty, to have both New York teams mothballed at the end while ragtag nines competed for the championship—oh, this was hard to bear.

How to view the Yankee season? As an Alex Rodriguez October brownout? A starting- pitcher collapse? A middle-relief meltdown? Yes, in some measure all such descriptions are apt. Granted, coming into the season the age and health of the starting rotation — Randy Johnson, Mike Mussina, Jaret Wright, Chien-Ming Wang, and Carl Pavano — were in question. But who knew that both corner outfielders and the second baseman would go down in mideaseason? Who knew that over the summer the Yanks would pull away from the Red Sox on the backs not only of Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Jason Giambi, and Johny Damon but also the likes of Melky Cabrera, Andy Phillips, and Brian Bruney?

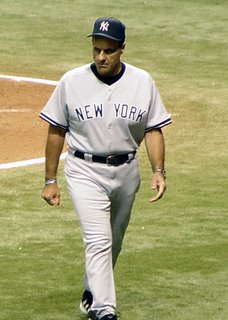

Joe Torre did his best job of managing this past year, and deserved to get a championship for holding the fort when he could have been forgiven for giving it up. So when the Yankees acquired Bobby Abreu and Corey Lidle to fill in for missing stars, and then saw a semblance of a return to form by Gary Sheffield and Hideki Matsui, fans might have been forgiven for regarding their team as a steamroller that could not be denied, The Greatest Lineup Ever Assembled, as Barnumesque sportswriters dubbed it.

But when the aging pitchers turned into pumpkins at midnight, Joe Torre and A-Rod turned out to be the unforgiven. George Steinbrenner even toyed with the idea of scapegoating his manager as he so often had in the past. But after a few tense days wiser heads in the democratized front office prevailed, and the future Hall of Fame helmsman will return for 2007. And here’s hoping that the “what have you done for me lately” crowd does not succeed in packing Rodriguez off to Chicago for Carlos Zambrano and prospects, as is currently rumored. The Yanks have a once-in-a-lifetime player in A-Rod, and at a bargain rate (improbable as that may seem), as the Texas Rangers are on the hook for nearly 40 percent of his $25.2 million annual salary.

The starting and middle relief crew will change — they must — or the boys of summer will again come to ruin in the fall. Below is a partial list of free-agent starting pitchers who might look good in pinstripes, even some who have worn them before

PAUL WILSON

TOMO OHKA

RAMON ORTIZ

GIL MECHE

TOM GLAVINE

JEFF SUPPAN

TONY ARMAS JR

JOSE CONTRERAS

JASON SCHMIDT

TED LILLY

MARK REDMAN

ANDY PETTITE

MARK MULDER

BARRY ZITO

DOUG DAVIS

RANDY WOLF

DAISUKE MATSUZAKA

Matsuzaka, the 26-year-old Japanese star who purports to throw a new pitch called the gyro ball (Al Leiter dismisses it as a cut fastball) is the prize in the bunch, but he will be very expensive, even more so for the Yankees because their payroll will expose them to a massive luxury tax. It was for this reason that they turned down Carlos Beltran two years ago because his $16 million per year would have a bottom-line cost to the Yankees in excess of $23 million. If they lose a bidding war for Zito they ought to go bargain hunting for Meche and Wolf.

That same shopping list will appeal to the Mets, even though it was their hitters who let them down in the League Championship Series against St. Louis. If the Mets elect not to pick up their $14 million option on the 40-year-old Glavine’s services — and prudence would dictate that they not — they will go into the 2007 season with ace Pedro Martinez still on the shelf after season-ending rotator cuff surgery and 40-year-old Orlando Herenandez returning as their lone veteran starter. Free agent Steve Trachsel will not return, and minor-league callup John Maine often looked like a deer in the headlights until magically, in October, he became a gazelle.

During the course of a season that saw the Mets send 13 men to the mound as starters—remember Alay Soler (8 starts), Jose Lima (4), and Geremi Gonzalez (3)? And then there were Brian Bannister (6), Dave Williams (5), Mike Pelfrey (4) and boo magnet Victor Zambrano (5). Last to be mentioned in this season-long cattle call for auditions, as the Mets cruised to the NL East flag, is Oliver Perez, a reclamation project who came to New York via Pittsburgh.

When El Duque joined Pedro on the sidelines before postseason play commenced, the Mets were forced to scramble. They swept the Dodgers as manager Willie Randolph brilliantly regarded his whole staff as a bullpen, bringing in relievers at the first sign that Maine and Trachsel might blow up. But after splitting the first two games with St. Louis, a blanking by Glavine and a too-short stint by Maine, the Mets’ prospects looked bleak. Had Franklin P. Adams been with us to opine on the scheduled Mets hurlers for the remainder of the Series, he might have written:

These are the saddest of possible words:

“Trachsel and Perez and Maine.”

Trio of pitchers, and sure for the birds,

“Trachsel and Perez and Maine.”

Ruthlessly pricking Mets’ gonfalon bubble,

Making a Cardinal walk into a double —

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

“Trachsel and Perez and Maine.”

Perez and Maine were hardly a modern-day “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain,” but they proved to be unexpectedly, preposterously effective. While the poet of “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon” would have been right about Trachsel, who gave a dreadful performance that will surely drive him out of New York, he would have been oh-so-wrong about the previously erratic Maine, who followed a weak outing by Glavine in Game 5 with a briliant one to keep hope alive in Flushing. Perez followed suit in Game 7, but did not walk awy with the palm because after a first-inning score the Mets went hitless until a ninth inning that still has Mets’ fans boiling. A miraculous catch by Endy Chavez, retrieving a certain home run from beyond the left-field wall in the seventh inning, was nearly forgotten.

Dominating the heart of the Cardinal order in the eighth frame, Aaron Heilman was left in to pitch the ninth despite the availability and itch to redeem himself of closer Bill Wagner, who had been awful in Games 2 and 5. Throwing a changeup that failed to dip, Heilman yielded a two-run homer to light-hitting Yadier Molina, and the second guessing rumbled through the grandstand onto the next day’s sports pages.

However, Randolph’s decision to stretch Heilman and withhold Wagner proved not as controversial as a call he was to make in the bottom of the frame, when the Mets mounted their ultimately futile rally. After Jose Valentin and Endy Chavez singled to open the inning against closer Adam Wainwright, the manager scorned the opportunity to bunt both men into scoring position. With Heilman due to bat, he might have asked Chris Woodward to sacrifice; instead he sent up injured slugger Cliff Floyd, who had been unable to play in the field since the early innings of Game 1.

Floyd was not going to bunt. Willie was looking for a Kirk Gibson moment. Instead he struck out. Peter King, writing for Sports Illustrated, opined, “Dumbest managerial move of the postseason: Willie Randolph sending up stale, injured and unable-to-bunt Cliff Floyd to pinch-hit with runners on first and second and no one out in the bottom of the ninth of Game 7, with the Mets down 3-1 and contact hitters Jose Reyes and Paul Lo Duca to follow. The only play there was to bunt the runners to second and third, but Floyd, looking old and ill-prepared, struck out looking. Just absurd.”

Peter King writes football. Baseball people, including Willie Randolph, knew that if Woodward had successfully bunted the men over to second and third, Reyes would have been walked, leaving the slow Lo Duca to confront a double-play situation.

Carlos Beltran was given the A-Rod treatment after he struck out looking to end the game. People complained, “Couldn’t he evn get his bat off his friggin’ shoulder?” No. The pitch was unhittable. As Mets’ GM Omar Minaya said, “People who say you have to swing at that are people who never played the game, who never stood in the batter’s box and faced a 90-plus-miles-per-hour fastball, then had the guy throw a curve.”

Willie Randolph and Joe Torre both did phenomenal jobs, bringing flawed, banged-up squads to the very edge of ultimate success. Next year, it says here, they’ll meet in the World Series.

With polo shirts and seersucker trousers stored in the attic for the next six months, it’s time to wrap up the baseball season too. The Cardinals and Tigers pecked and clawed at each other for five more desultory evenings, but when viewed through Gotham-colored glasses, the national pastime of 2006 had concluded some time before.

Laid away for winter storage, each memory is briefly savored or rued on the way to being forgotten. And with the Mets and Yankees it is the regret, not the joy, that lingers; long distant is the confidence of summer, when each had emerged as the best team in its league. While all but the credulous knew that a Subway Series was no certainty, to have both New York teams mothballed at the end while ragtag nines competed for the championship—oh, this was hard to bear.

How to view the Yankee season? As an Alex Rodriguez October brownout? A starting- pitcher collapse? A middle-relief meltdown? Yes, in some measure all such descriptions are apt. Granted, coming into the season the age and health of the starting rotation — Randy Johnson, Mike Mussina, Jaret Wright, Chien-Ming Wang, and Carl Pavano — were in question. But who knew that both corner outfielders and the second baseman would go down in mideaseason? Who knew that over the summer the Yanks would pull away from the Red Sox on the backs not only of Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Jason Giambi, and Johny Damon but also the likes of Melky Cabrera, Andy Phillips, and Brian Bruney?

Joe Torre did his best job of managing this past year, and deserved to get a championship for holding the fort when he could have been forgiven for giving it up. So when the Yankees acquired Bobby Abreu and Corey Lidle to fill in for missing stars, and then saw a semblance of a return to form by Gary Sheffield and Hideki Matsui, fans might have been forgiven for regarding their team as a steamroller that could not be denied, The Greatest Lineup Ever Assembled, as Barnumesque sportswriters dubbed it.

But when the aging pitchers turned into pumpkins at midnight, Joe Torre and A-Rod turned out to be the unforgiven. George Steinbrenner even toyed with the idea of scapegoating his manager as he so often had in the past. But after a few tense days wiser heads in the democratized front office prevailed, and the future Hall of Fame helmsman will return for 2007. And here’s hoping that the “what have you done for me lately” crowd does not succeed in packing Rodriguez off to Chicago for Carlos Zambrano and prospects, as is currently rumored. The Yanks have a once-in-a-lifetime player in A-Rod, and at a bargain rate (improbable as that may seem), as the Texas Rangers are on the hook for nearly 40 percent of his $25.2 million annual salary.

The starting and middle relief crew will change — they must — or the boys of summer will again come to ruin in the fall. Below is a partial list of free-agent starting pitchers who might look good in pinstripes, even some who have worn them before

PAUL WILSON

TOMO OHKA

RAMON ORTIZ

GIL MECHE

TOM GLAVINE

JEFF SUPPAN

TONY ARMAS JR

JOSE CONTRERAS

JASON SCHMIDT

TED LILLY

MARK REDMAN

ANDY PETTITE

MARK MULDER

BARRY ZITO

DOUG DAVIS

RANDY WOLF

DAISUKE MATSUZAKA

Matsuzaka, the 26-year-old Japanese star who purports to throw a new pitch called the gyro ball (Al Leiter dismisses it as a cut fastball) is the prize in the bunch, but he will be very expensive, even more so for the Yankees because their payroll will expose them to a massive luxury tax. It was for this reason that they turned down Carlos Beltran two years ago because his $16 million per year would have a bottom-line cost to the Yankees in excess of $23 million. If they lose a bidding war for Zito they ought to go bargain hunting for Meche and Wolf.

That same shopping list will appeal to the Mets, even though it was their hitters who let them down in the League Championship Series against St. Louis. If the Mets elect not to pick up their $14 million option on the 40-year-old Glavine’s services — and prudence would dictate that they not — they will go into the 2007 season with ace Pedro Martinez still on the shelf after season-ending rotator cuff surgery and 40-year-old Orlando Herenandez returning as their lone veteran starter. Free agent Steve Trachsel will not return, and minor-league callup John Maine often looked like a deer in the headlights until magically, in October, he became a gazelle.

During the course of a season that saw the Mets send 13 men to the mound as starters—remember Alay Soler (8 starts), Jose Lima (4), and Geremi Gonzalez (3)? And then there were Brian Bannister (6), Dave Williams (5), Mike Pelfrey (4) and boo magnet Victor Zambrano (5). Last to be mentioned in this season-long cattle call for auditions, as the Mets cruised to the NL East flag, is Oliver Perez, a reclamation project who came to New York via Pittsburgh.

When El Duque joined Pedro on the sidelines before postseason play commenced, the Mets were forced to scramble. They swept the Dodgers as manager Willie Randolph brilliantly regarded his whole staff as a bullpen, bringing in relievers at the first sign that Maine and Trachsel might blow up. But after splitting the first two games with St. Louis, a blanking by Glavine and a too-short stint by Maine, the Mets’ prospects looked bleak. Had Franklin P. Adams been with us to opine on the scheduled Mets hurlers for the remainder of the Series, he might have written:

These are the saddest of possible words:

“Trachsel and Perez and Maine.”

Trio of pitchers, and sure for the birds,

“Trachsel and Perez and Maine.”

Ruthlessly pricking Mets’ gonfalon bubble,

Making a Cardinal walk into a double —

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

“Trachsel and Perez and Maine.”

Perez and Maine were hardly a modern-day “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain,” but they proved to be unexpectedly, preposterously effective. While the poet of “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon” would have been right about Trachsel, who gave a dreadful performance that will surely drive him out of New York, he would have been oh-so-wrong about the previously erratic Maine, who followed a weak outing by Glavine in Game 5 with a briliant one to keep hope alive in Flushing. Perez followed suit in Game 7, but did not walk awy with the palm because after a first-inning score the Mets went hitless until a ninth inning that still has Mets’ fans boiling. A miraculous catch by Endy Chavez, retrieving a certain home run from beyond the left-field wall in the seventh inning, was nearly forgotten.

Dominating the heart of the Cardinal order in the eighth frame, Aaron Heilman was left in to pitch the ninth despite the availability and itch to redeem himself of closer Bill Wagner, who had been awful in Games 2 and 5. Throwing a changeup that failed to dip, Heilman yielded a two-run homer to light-hitting Yadier Molina, and the second guessing rumbled through the grandstand onto the next day’s sports pages.

However, Randolph’s decision to stretch Heilman and withhold Wagner proved not as controversial as a call he was to make in the bottom of the frame, when the Mets mounted their ultimately futile rally. After Jose Valentin and Endy Chavez singled to open the inning against closer Adam Wainwright, the manager scorned the opportunity to bunt both men into scoring position. With Heilman due to bat, he might have asked Chris Woodward to sacrifice; instead he sent up injured slugger Cliff Floyd, who had been unable to play in the field since the early innings of Game 1.

Floyd was not going to bunt. Willie was looking for a Kirk Gibson moment. Instead he struck out. Peter King, writing for Sports Illustrated, opined, “Dumbest managerial move of the postseason: Willie Randolph sending up stale, injured and unable-to-bunt Cliff Floyd to pinch-hit with runners on first and second and no one out in the bottom of the ninth of Game 7, with the Mets down 3-1 and contact hitters Jose Reyes and Paul Lo Duca to follow. The only play there was to bunt the runners to second and third, but Floyd, looking old and ill-prepared, struck out looking. Just absurd.”

Peter King writes football. Baseball people, including Willie Randolph, knew that if Woodward had successfully bunted the men over to second and third, Reyes would have been walked, leaving the slow Lo Duca to confront a double-play situation.

Carlos Beltran was given the A-Rod treatment after he struck out looking to end the game. People complained, “Couldn’t he evn get his bat off his friggin’ shoulder?” No. The pitch was unhittable. As Mets’ GM Omar Minaya said, “People who say you have to swing at that are people who never played the game, who never stood in the batter’s box and faced a 90-plus-miles-per-hour fastball, then had the guy throw a curve.”

Willie Randolph and Joe Torre both did phenomenal jobs, bringing flawed, banged-up squads to the very edge of ultimate success. Next year, it says here, they’ll meet in the World Series.

--John Thorn

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Cardboard Gods

From "Play's the Thing," Woodstock Times, October 12, 2006:

I was a newcomer to this country in 1949, a German-speaking boy trying to fit in as an American. My parents had conceived me in a displaced persons camp in Stuttgart as affirmation of their survival and as revenge against Hitler. Somehow they conveyed to me very early on that the world was not a safe place and that caution and seclusion were essential life skills. Thus reticent by nature and circumstance, all the same I longed for risk and inclusion.

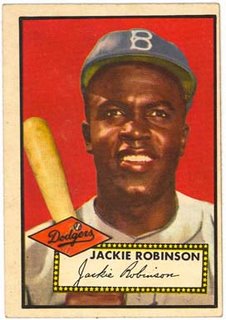

Baseball cards were my way in, and my way out. These cardboard gods were my tickets of admission to the street games of the Bronx and passports to a larger sense of being somehow American. I learned to read from the backs of the cards, those magically encapsulated hagiographies, and discovered I had an unusual memory for facts and figures that in the older gang into which I sought admission lent me the jester’s motley of amusement and license. I flipped cards passably, too, and delighted in winning a Jackie Robinson while risking only a Wally Westlake. Cards were currency in more ways than one.

My parents of course viewed my street-corner competitions as unserious and unworthy—if I were such a prodigy that I could read baseball cards, why not the Talmud? Chubby and unathletic, I was permanently “it” in games of tag and a figure of fun at Hopscotch or Ringolevio. Until my teen years when, sprouted and slimmed, I was miraculously able to play the game I had known only through its fetishes, my bubble-gum cards provided safe passage through rings and ring leaders. Like all games, as I was later to learn, they provided early instruction in the rules of adult society: mimicking its rules of inclusion and exclusion, sublimating its rites of war, and creating a bazaar of barter and status.

Fast forward half a century. The games that had connected a lonely boy to his peers and had provided a peephole into the adult world—what do men DO?, a boy wondered—now connect a grandfather to his youth, with reminiscent pleasure, certainly, but always questions, questions. Now a historian of sport, an analyst of play, I collect stories rather than cards as my trophies. And I recently came across a good one, in an 1891 issue of The American Journal of Folklore (today known as The Journal of American Folklore) by Stewart Culin, one of the giants of folklore studies but heretofore unknown to me.

As with the long-standing question of when baseball began, to which I have been supplying tentative answers for some time, I had wondered when baseball-card flipping and trading commenced. For me it was 1952, but I knew that in the 1880s photographic and chromolith cards were inserted into cigarette packs, whose purchasers were presumably not children. Culin, in “Street Games of Boys in Brooklyn, New York,” cites thirty-six games described to him by “a lad of ten years, residing in the city of Brooklyn, N. Y., as games in which he himself had taken part.” From Hare and Hounds to Red Rover, from Leap Frog to Kick the Can, Culin details games that many of us recall from our own youths, however many years since. The thirty-sixth game I relate verbatim:

“PICTURES: This game is a recent invention, and is played with the small picture cards which the manufacturers of cigarettes have distributed with their wares for some years past. These pictures, which are nearly uniform in size and embrace a great variety of subjects, are eagerly collected by boys in Brooklyn and the near-by cities, and form an article of traffic among them. Bounds are marked of about twelve by eight feet, with a wall or stoop at the back. The players stand at the longer distance, and each in turn shoots a card with his fingers, as he would a marble, against the wall or stoop. The one whose card goes nearest that object collects all the cards that have been thrown, and twirls them either singly or together into the air. Those that fall with the picture up belong to him, according to the rules; while those that fall with the reverse side uppermost are handed to the player whose card came next nearest to the wall, and he in turn twirls them, and receives those that fall with the picture side up. The remainder, if any, are taken by the next nearest player, and the game continues until the cards thrown are divided.”

Boys badgered men coming out of tobacconist shops for the pictures in their cigarette packs, or they took up smoking early, incentivized by the lure of the cards. That the cards were worthless to most adults may have added to their value for children … such is the spin of generations. Once it became clear who the “customers” for the cards truly were, the candy and gum manufacturers got into the act, including cards with their products; by 1920 or so baseball cards ceased to be packed in with cigarettes. The cards entered a golden age that coincided with my own boyhood of the 1950s, as the Topps Gum Company issued cards of surpassing charm that today are auctioned at Sotheby’s rather than skipped over pavement to lean against apartment-house walls.

Card-flipping was clearly a game of the city, where sidewalks outnumbered grassy fields or even sandlots. Culin, a picturesque writer, notes that like other street games, it had been “modified to suit the circumstances of city life, where paved streets and iron lampposts and telegraph poles take the place of the village common, fringed with forest trees, and Nature, trampled on and suppressed, most vividly reasserts herself in the shouts of the children….” Card flipping in my boyhood was not baseball, surely, and yet as its surrogate it retained something of the larger game’s spell. There was joy and reverence in the handling of our totems, some of whom we withheld from corner-clipping confrontations unless the reward equaled the risk.

We were oasis traders more than we were ball players, but we felt we were a part of the game. Duke Snider and the Dodgers were sure to prevail at Ebbets Field if an artful wrist-snap could lean him against the stoop, vanquishing all the cards beneath him. And in the power transference that accompanies such magical acts, we were heroes too.

I was a newcomer to this country in 1949, a German-speaking boy trying to fit in as an American. My parents had conceived me in a displaced persons camp in Stuttgart as affirmation of their survival and as revenge against Hitler. Somehow they conveyed to me very early on that the world was not a safe place and that caution and seclusion were essential life skills. Thus reticent by nature and circumstance, all the same I longed for risk and inclusion.

Baseball cards were my way in, and my way out. These cardboard gods were my tickets of admission to the street games of the Bronx and passports to a larger sense of being somehow American. I learned to read from the backs of the cards, those magically encapsulated hagiographies, and discovered I had an unusual memory for facts and figures that in the older gang into which I sought admission lent me the jester’s motley of amusement and license. I flipped cards passably, too, and delighted in winning a Jackie Robinson while risking only a Wally Westlake. Cards were currency in more ways than one.

My parents of course viewed my street-corner competitions as unserious and unworthy—if I were such a prodigy that I could read baseball cards, why not the Talmud? Chubby and unathletic, I was permanently “it” in games of tag and a figure of fun at Hopscotch or Ringolevio. Until my teen years when, sprouted and slimmed, I was miraculously able to play the game I had known only through its fetishes, my bubble-gum cards provided safe passage through rings and ring leaders. Like all games, as I was later to learn, they provided early instruction in the rules of adult society: mimicking its rules of inclusion and exclusion, sublimating its rites of war, and creating a bazaar of barter and status.

Fast forward half a century. The games that had connected a lonely boy to his peers and had provided a peephole into the adult world—what do men DO?, a boy wondered—now connect a grandfather to his youth, with reminiscent pleasure, certainly, but always questions, questions. Now a historian of sport, an analyst of play, I collect stories rather than cards as my trophies. And I recently came across a good one, in an 1891 issue of The American Journal of Folklore (today known as The Journal of American Folklore) by Stewart Culin, one of the giants of folklore studies but heretofore unknown to me.

As with the long-standing question of when baseball began, to which I have been supplying tentative answers for some time, I had wondered when baseball-card flipping and trading commenced. For me it was 1952, but I knew that in the 1880s photographic and chromolith cards were inserted into cigarette packs, whose purchasers were presumably not children. Culin, in “Street Games of Boys in Brooklyn, New York,” cites thirty-six games described to him by “a lad of ten years, residing in the city of Brooklyn, N. Y., as games in which he himself had taken part.” From Hare and Hounds to Red Rover, from Leap Frog to Kick the Can, Culin details games that many of us recall from our own youths, however many years since. The thirty-sixth game I relate verbatim:

“PICTURES: This game is a recent invention, and is played with the small picture cards which the manufacturers of cigarettes have distributed with their wares for some years past. These pictures, which are nearly uniform in size and embrace a great variety of subjects, are eagerly collected by boys in Brooklyn and the near-by cities, and form an article of traffic among them. Bounds are marked of about twelve by eight feet, with a wall or stoop at the back. The players stand at the longer distance, and each in turn shoots a card with his fingers, as he would a marble, against the wall or stoop. The one whose card goes nearest that object collects all the cards that have been thrown, and twirls them either singly or together into the air. Those that fall with the picture up belong to him, according to the rules; while those that fall with the reverse side uppermost are handed to the player whose card came next nearest to the wall, and he in turn twirls them, and receives those that fall with the picture side up. The remainder, if any, are taken by the next nearest player, and the game continues until the cards thrown are divided.”

Boys badgered men coming out of tobacconist shops for the pictures in their cigarette packs, or they took up smoking early, incentivized by the lure of the cards. That the cards were worthless to most adults may have added to their value for children … such is the spin of generations. Once it became clear who the “customers” for the cards truly were, the candy and gum manufacturers got into the act, including cards with their products; by 1920 or so baseball cards ceased to be packed in with cigarettes. The cards entered a golden age that coincided with my own boyhood of the 1950s, as the Topps Gum Company issued cards of surpassing charm that today are auctioned at Sotheby’s rather than skipped over pavement to lean against apartment-house walls.

Card-flipping was clearly a game of the city, where sidewalks outnumbered grassy fields or even sandlots. Culin, a picturesque writer, notes that like other street games, it had been “modified to suit the circumstances of city life, where paved streets and iron lampposts and telegraph poles take the place of the village common, fringed with forest trees, and Nature, trampled on and suppressed, most vividly reasserts herself in the shouts of the children….” Card flipping in my boyhood was not baseball, surely, and yet as its surrogate it retained something of the larger game’s spell. There was joy and reverence in the handling of our totems, some of whom we withheld from corner-clipping confrontations unless the reward equaled the risk.

We were oasis traders more than we were ball players, but we felt we were a part of the game. Duke Snider and the Dodgers were sure to prevail at Ebbets Field if an artful wrist-snap could lean him against the stoop, vanquishing all the cards beneath him. And in the power transference that accompanies such magical acts, we were heroes too.

--John Thorn