Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Meet the Mets

From "Play's the Thing," Woodstock Times, March 30, 2006:

The bickering Thorns are at it again, undaunted by our failure to pick last year’s Super Bowl winner. We correctly tabbed Seattle to top the NFC, but who could have figured the wild-card Steelers to win it all? Probably the same guy who picked George Mason to make it to the Final Four, but as he is not proposing to write this column, we must.

Here is the Official Father-Son take on the 2006 baseball season. Preseason picks can be, like George Bernard Shaw’s take on second marriages, the triumph of hope over experience. While we Thorns confess to being Mets fans, we have not donned rose-colored glasses. This is just their year.

In the divisional wrap-ups below, teams are listed in the order of their predicted finish.

AL EAST

Boston Red Sox: Of all the moves the Carmine Hose made in the off-season, to many the most puzzling was sending pitcher Bronson Arroyo to the Reds in return for enigmatic 24-year old Wily Mo Pena. Boston seemed short of pitching and long on offense. We think it was a brilliant move. Do not be surprised if Pena hits more than 25 home runs as a fourth outfielder and challenges Trot Nixon for the right-field spot. Coco Crisp will make Boston fans scratch their heads to recall who played center field last year. Mark Loretta and J.T. Snow will pay big dividends. If Curt Schilling, Josh Beckett, and Tim Wakefield win 15 each, the retooled Red Sox win the division. Manny Ramirez will be his usual three-ring circus, but he is not Terrell Owens: at the end of the day his numbers make anything endurable, in any clubhouse.

New York Yankees: Although the Yankees have more talent than Boston in some areas, their fragility makes us shy away from picking them as AL East champions. Randy Johnson remains a dominant pitcher, but it would be hard to pick an over-under on how many times he’ll be healthy enough to toe the mound. Slipping production from Mike Mussina plus Carl Pavano’s constant health problems also make the rotation seem shaky. Aaron Small will not go 10-0 again, and Shawn Chacon may also prove a one-year wonder. Alex Rodriguez will have another monster year and carry the offensive load with Gary Sheffield. The addition of Johnny Damon certainly plugs a hole defensively and he will be a fine leadoff hitter, enabling Derek Jeter to bat second, for which his style is better suited. We wouldn’t be surprised to see the Yankees win the division. It’s just that age and injury hang over this club like a Damoclean sword.

Toronto Blue Jays: Adding Lyle Overbay, Troy Glaus, and Bengie Molina should benefit the offense just as much as the signings of B.J. Ryan and A.J. Burnett will help Roy Halladay and the rest of the pitching staff. Yet holdover Vernon Wells remains the team’s key to success. With Alex Rios and Frank Catalanotto manning the corner outfield spots, Wells is going to have to have a break out year for power. Starting pitching is a little bit thin past the two-spot. This may be the most improved team in baseball, yet they fall short of securing a wild-card berth.

Baltimore Orioles: The Orioles took a flier on Corey Patterson to start in center field, and if he doesn’t live up to his eternally dangled potential, this team is in for a long one. By signing Ramon Hernandez, Javy Lopez will catch fewer games and giv ethe club more at bats, a good move. Melvin Mora is a great player, and so is Miguel Tejada. It remains to be seen if Brian Roberts has completely recovered from his gruesome shoulder injury. The starting pitching is adequate at best, even with the addition of Kris Benson. Now that BJ Ryan is a Blue Jay, they will also need to anoint a new closer. It seems to us that even if Tejada and Mora have huge years, the Birds’ pitching will condemn them to a sub-.500 record.

Tampa Bay Devil Rays: This team would finish in last place in any division in Major League Baseball. Rocco Baldelli, Jorge Cantu and Carl Crawford continue to blossom. Expect Mets’ fans across the country to hurl beer bottles through their televisions as they catch clips of phenom Scott Kazmir’s development into an elite starter. Still, glimmers of hope will be of no consequence. Julio Lugo will probably be moved by the trading deadline, and the majority of Tampa Bay’s roster consists of unknowns and cast-offs. They gave up on Dewon Brazelton, which makes little sense given the composition of their pitching corps.

AL CENTRAL

Chicago White Sox: Re-signing first basemen Paul Konerko was extremely prudent. If Jim Thome hits decently and stays healthy it’ll be more than what the oft-injured and much maligned Frank Thomas did over the last few years. Ozzie Guillen’s pitching staff may be the best in baseball, even if Jon Garland and Mark Buehrle come back to earth a bit. After winning a championship, teams usually lose more than this club did. The Indians will be hot on their heels again, but the Chisox are poised to dominate the division for the next few years with the core they have.

Cleveland Indians: If nothing else, the 2006 season should be just as exciting as last year’s wild-card chase was. The young talent of this team is as good as any in the game. If Travis Hafner hadn’t gotten hit in the head during last year’s playoff chase, who is to say Cleveland wouldn’t have taken the division? Victor Martinez is a great young catcher. Cliff Lee is a legitimate ace, and C.C. Sabathia will also eat up a lot of innings. A Division Championship might be a bit of a stretch, but earning a Wild Card berth certainly isn’t.

Minnesota Twins: Concerns abound in Minnesota. Johan Santana and Brad Radke anchor a decent staff, which will keep them in most games. This team’s two biggest concerns are the health of Torii Hunter and the development of catcher Joe Mauer. This will be a competitive club, but they lack in power. Pitching will keep this team in contention for the majority of the year, but it remains to be seen how this team will put runs on the board. Jacque Jones’s departure leaves the middle of the Minnesota lineup thin.

Detroit Tigers: Placido Polanco will have a good year, and should be a good player for quite some time. Pudge Rodriguez is doing his best to be a leader and producer. The Tigers are showing signs of life, but they are still several years and players away. Magglio Ordonez is looking to rebound from an injury shortened ’05 campaign, and should put up numbers if he is able to shake the injury bug. Kenny Rogers will eat up innings, and possibly mentor the rest of the young Tigers’ staff. The Ugueth Urbina “Machete Madness Party” left a hole where the bullpen used to be, and there isn’t anything this team can do to finish better than fourth in the Central.

Kansas City Royals: Pitcher Zack Greinke briefly left spring training “for personal reasons.” Can’t say the thought of running away from the Royals wouldn’t cross our minds. When the prize free agency signing your franchise touts is the fossilized remains of Reggie Sanders, you know the win total is going to be in the 70s. Young talent on the roster will leave town as soon as possible. There really isn’t much to say about this franchise and competitive baseball unless you want to take it back to the days of their pale blue jerseys and cassette tapes.

AL WEST

Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim: The tandem of Vladimir Guerrero and Bartolo Colon alone should be enough to secure another division title. Last year’s divisional champs lost some veteran talent but have correctly assessed that room had to be made for their talented farmhands Jeff Mathis, Dallas Macpherson and Casey Kotchman. Chone Figgins is one of the most underrated players in the league. He’s like Jose Oquendo with top-flight skills.

Oakland Athletics: We’re rooting for Frank Thomas to stay healthy and hit 40 home runs. Expect big seasons from pitchers Rich Harden and Danny Haren, but also expect Barry Zito to be elsewhere at the All-Star break. Huston Street is one of the most exciting young closers in the league, and this staff should be able to get the ball into his hands often enough. But where are the outfield bats? Shortstop Bobby Crosby’s health is also a significant issue. If this team does eke out a wild-card berth, they will be bounced from the first round.

Texas Rangers: Runs are going to be scored. In bunches. Kevin Millwood should replace Kenny Rogers just fine. He’ll probably be better received by cameramen as well. Hank Blalock and Mark Texiera will launch dozens upon dozens of homeruns, but it’s going to be more of the same in Arlington. Until Texas gets more quality starts from their staff, they aren’t going to return to postseason play. If they can keep their tandem of young sluggers under contract and bring in some midlevel pitching they will be able to contend in a few years.

Seattle Mariners: No matter what sort of offensive production new catcher Kenji Johjima provides, the language gap with the pitching staff is going to take a toll over the duration of the season. Richie Sexson and Adrian Beltre will probably have solid years, and so will Ichiro, but the sinew in the batting order just isn’t there anymore. When Seattle was very successful, they had guys like Jay Buhner to serve as support to the bigger talents in the lineup. For the kind of ballpark Safeco is, this team’s composition isn’t a dreamy match. Jamie Moyer will squeeze another year out of his aging body, but this team is going to have to wallow in the cellar for a few years with what they have.

NL EAST

New York Mets: It comes down in large part to the Carloses. If Delgado stays healthy and Beltran has a better year, this team will end the Braves’ endless string of NL East titles. We’ll hear more than enough about Pedro Martinez’s toe. The addition of Billy Wagner gives the Mets their most reliable closer since Randy Myers. Expectations and the payroll are high, but this is the year for the Mets to shine. Infielders Jose Reyes and David Wright will improve both at the bat and in the field. New catcher Paul Lo Duca will throw out some runners. And middle relief, until some brilliant offseason moves the team’s weak spot, will prove to be the league’s best.

Atlanta Braves: The song remains the same. The roster changes yearly, yet Bobby Cox gets the most out of what he has. Jeff Francoeur continues to emerge as one of the best right fielders in the game. It remains to be seen if Edgar Renteria will be the All Star he was as a Cardinal, or the error machine he was while with the Red Sox. John Smoltz and Tim Hudson are as good as any front end of a rotation. Unfortunately for Atlanta, New York’s offense is far superior.

Philadelphia Phillies: Ryan Howard is as impressive a young slugger as you will find in the game today. Jimmy Rollins will continue his solid play though not his 2005 batting streak. We’ll see if all the trade rumors affect Bobby Abreu, and watch as their marginal pitching staff keeps them from excelling. Tom Gordon closing might not work out so well either.

Washington Nationals: The combustive personalities of Jose Guillen and Alfonso Soriano in one clubhouse does not bode well for team chemistry, or high numbers in the win column. Cristian Guzman is the new Rey Ordonez. Livan Hernandez is counted on to be the ace, again, and to throw too many innings, again. This squad overachieved last year, but their true colors (and paltry offense) will show. You’ll hear more about off-the-field bickering than you will about anything else. Unless it’s the trade of Soriano or Jose Vidro to the Mets...

Florida Marlins: Joe Girardi sure fell for the ol’ bait-and-switch on this one. After the ex-Yank was hired as manager, the systematic dissolution of the team began. It is highly likely that Dontrelle Willis and Miguel Cabrera will be moved. No one wants to sit in the Miami sun or evening murk to watch a game. Even though this team has won two world championships recently, they are dead in the water. Until an ownership group steps up and moves this team, it’s going to be all bad. At the rate this team is being scrapped, Girardi might find himself catching by the end of the year.

NL CENTRAL

St. Louis Cardinals: This team is good enough to contend in any division, but since they’re in the oh-so-weak Central it’s going to be a cakewalk. Expect St. Louis to win the division by more than a dozen games. Albert Pujols is one of the three best players in the league, and there isn’t going to be anyone breathing down this club’s neck much past the All Star break. It’s really too bad that the Cardinals are always ho-humming by the time the playoffs roll around, because in the era of the wild card, momentum in September means a lot to how a team plays in October.

Houston Astros: As NASA would say, the window has closed. The Roger Clemens experience is over, as is Jeff Bagwell’s career. This team might contend for a wild card, but if Andy Pettite gets hurt it’s over. Willy Taveras is an exciting player who should continue to develop. Count on Brad Lidge to bounce back from his playoff blowup. The addition of Preston Wilson isn’t going to put this team over the top.

Milwaukee Brewers: As their superb young talent continues to develop, their record will improve. If you’re looking for a Cinderella (or George Mason) story, you could do worse than picking the Brew Crew to take the wild card. Prince Fielder and Richie Weeks are going to be perennial All Stars. However, if the race for the playoffs is tight in September, count on the Astros to prevail this year.

Chicago Cubs: Dusty Baker’s head is going to roll this summer. The Chicago media has been calling for it for years, and the expected injuries to Kerry Wood and Mark Prior are going to make the axe fall. The White Sox winning the Series last year didn’t exactly appease Cubs fans’ desire to win one. As long as this club’s success is tied to the balky bodies of their two young aces, the drought will continue.

Cincinnati Reds: Eric Milton may be the worst starting pitcher in baseball. Expect him to challenge Bert Blyleven’s record for most homers surrendered in a year, while doubling Blyleven’s ERA. New ownership may right this ship eventually, but it’s not a one year plan. The pitching staff is laughable, even with the acquisition of Bronson Arroyo. Combine the sketchiness of the rotation with their outfielders’ inability to stay healthy, and the result is another year of high-scoring losses. This club reminds one of the 1930 Phillies.

Pittsburgh Pirates: Ouch is all you can say when looking at this team. Anything short of time warping and bringing back a young Barry Bonds or Willie Stargell just won’t do. Jason Bay is a solid player, but teams on which Joe Randa is an Opening Day starter do not fare well. Suggested trade: swap entire roster for that of the Tampa Bay Devil Rays and see whether playing in a decent home ballpark makes a difference.

NL WEST

San Diego Padres: Mike Cameron deserves to play center field again, and The City Where the Weather Never Changes should make for a nice change from New York. The fates would have it for him to do so at the same field where he nearly ended his baseball career last summer. Mike Piazza finally is free of expectations, and should do well as the marquee player on his new club. This is a division which can be won by a team with a losing record. If San Diego played in a different division, they might struggle to make the postseason. In the NL West, an 85-win team is king.

Los Angeles Dodgers: Kenny Lofton will be old enough to get a 15% discount at IHOP by the end of the year, so having him start in center field might not be the best plan. We’re rooting for Nomar Garciaparra to resurrect his career in LA while learning how to play first base. Safest prediction in the bunch: Jeff Kent will fight someone in Dodger blue. If J.D. Drew plays more than 145 games this year confetti should drop from the sky. Ever since the team acquired Darryl Strawberry, clubhouse chemistry has been rocky or nonexistent.

San Francisco Giants: Barry Bonds could hit 10 or 60 home runs this year, but he can’t pitch while doing it. Omar Vizquel, Steve Finley and the rest of the over-the-hill gang can not protect Bonds in the lineup (assuming he can even play). This year will be nothing but an orgy of media attention focused on Barry’s off-the-field issues, and that can’t help the team.

Arizona Diamondbacks: There isn’t a lot of good going on in Arizona right now. Orlando Hudson looks to have a bounce-back year, but this team is pretty devoid of upcoming talent. Names like Shawn Green and Luis Gonzalez look good on paper, but there’s not much left in their tanks.

Colorado Rockies: Another expansion debacle, this team will likely never be competitive. With the altitude induced long balls, the demoralized pitching staff this team will resemble a backyard Whiffle ball squad more than a major league one. Rockies pitchers show their stuff before they get here and after they leave. One wonders what kind of numbers Todd Helton would put up if he didn’t play in Colorado. One wonders whether the league will allow a special dead ball to be used in Rockies home games. One also wonders if this team will win 70 games.

DIVISIONAL PLAYOFFS: Mets over Astros

DIVISIONAL PLAYOFFS: Cardinals over Padres

NLCS: Mets over Cardinals

DIVISIONAL PLAYOFFS: Angels over Red Sox

DIVISIONAL PLAYOFFS: Yankees over White Sox

ALCS: Angels over Yankees

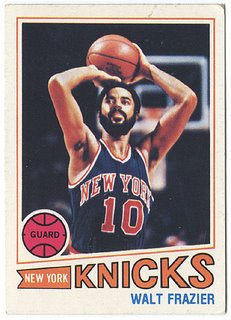

WORLD SERIES: Mets over Angels in 6

The bickering Thorns are at it again, undaunted by our failure to pick last year’s Super Bowl winner. We correctly tabbed Seattle to top the NFC, but who could have figured the wild-card Steelers to win it all? Probably the same guy who picked George Mason to make it to the Final Four, but as he is not proposing to write this column, we must.

Here is the Official Father-Son take on the 2006 baseball season. Preseason picks can be, like George Bernard Shaw’s take on second marriages, the triumph of hope over experience. While we Thorns confess to being Mets fans, we have not donned rose-colored glasses. This is just their year.

In the divisional wrap-ups below, teams are listed in the order of their predicted finish.

AL EAST

Boston Red Sox: Of all the moves the Carmine Hose made in the off-season, to many the most puzzling was sending pitcher Bronson Arroyo to the Reds in return for enigmatic 24-year old Wily Mo Pena. Boston seemed short of pitching and long on offense. We think it was a brilliant move. Do not be surprised if Pena hits more than 25 home runs as a fourth outfielder and challenges Trot Nixon for the right-field spot. Coco Crisp will make Boston fans scratch their heads to recall who played center field last year. Mark Loretta and J.T. Snow will pay big dividends. If Curt Schilling, Josh Beckett, and Tim Wakefield win 15 each, the retooled Red Sox win the division. Manny Ramirez will be his usual three-ring circus, but he is not Terrell Owens: at the end of the day his numbers make anything endurable, in any clubhouse.

New York Yankees: Although the Yankees have more talent than Boston in some areas, their fragility makes us shy away from picking them as AL East champions. Randy Johnson remains a dominant pitcher, but it would be hard to pick an over-under on how many times he’ll be healthy enough to toe the mound. Slipping production from Mike Mussina plus Carl Pavano’s constant health problems also make the rotation seem shaky. Aaron Small will not go 10-0 again, and Shawn Chacon may also prove a one-year wonder. Alex Rodriguez will have another monster year and carry the offensive load with Gary Sheffield. The addition of Johnny Damon certainly plugs a hole defensively and he will be a fine leadoff hitter, enabling Derek Jeter to bat second, for which his style is better suited. We wouldn’t be surprised to see the Yankees win the division. It’s just that age and injury hang over this club like a Damoclean sword.

Toronto Blue Jays: Adding Lyle Overbay, Troy Glaus, and Bengie Molina should benefit the offense just as much as the signings of B.J. Ryan and A.J. Burnett will help Roy Halladay and the rest of the pitching staff. Yet holdover Vernon Wells remains the team’s key to success. With Alex Rios and Frank Catalanotto manning the corner outfield spots, Wells is going to have to have a break out year for power. Starting pitching is a little bit thin past the two-spot. This may be the most improved team in baseball, yet they fall short of securing a wild-card berth.

Baltimore Orioles: The Orioles took a flier on Corey Patterson to start in center field, and if he doesn’t live up to his eternally dangled potential, this team is in for a long one. By signing Ramon Hernandez, Javy Lopez will catch fewer games and giv ethe club more at bats, a good move. Melvin Mora is a great player, and so is Miguel Tejada. It remains to be seen if Brian Roberts has completely recovered from his gruesome shoulder injury. The starting pitching is adequate at best, even with the addition of Kris Benson. Now that BJ Ryan is a Blue Jay, they will also need to anoint a new closer. It seems to us that even if Tejada and Mora have huge years, the Birds’ pitching will condemn them to a sub-.500 record.

Tampa Bay Devil Rays: This team would finish in last place in any division in Major League Baseball. Rocco Baldelli, Jorge Cantu and Carl Crawford continue to blossom. Expect Mets’ fans across the country to hurl beer bottles through their televisions as they catch clips of phenom Scott Kazmir’s development into an elite starter. Still, glimmers of hope will be of no consequence. Julio Lugo will probably be moved by the trading deadline, and the majority of Tampa Bay’s roster consists of unknowns and cast-offs. They gave up on Dewon Brazelton, which makes little sense given the composition of their pitching corps.

AL CENTRAL

Chicago White Sox: Re-signing first basemen Paul Konerko was extremely prudent. If Jim Thome hits decently and stays healthy it’ll be more than what the oft-injured and much maligned Frank Thomas did over the last few years. Ozzie Guillen’s pitching staff may be the best in baseball, even if Jon Garland and Mark Buehrle come back to earth a bit. After winning a championship, teams usually lose more than this club did. The Indians will be hot on their heels again, but the Chisox are poised to dominate the division for the next few years with the core they have.

Cleveland Indians: If nothing else, the 2006 season should be just as exciting as last year’s wild-card chase was. The young talent of this team is as good as any in the game. If Travis Hafner hadn’t gotten hit in the head during last year’s playoff chase, who is to say Cleveland wouldn’t have taken the division? Victor Martinez is a great young catcher. Cliff Lee is a legitimate ace, and C.C. Sabathia will also eat up a lot of innings. A Division Championship might be a bit of a stretch, but earning a Wild Card berth certainly isn’t.

Minnesota Twins: Concerns abound in Minnesota. Johan Santana and Brad Radke anchor a decent staff, which will keep them in most games. This team’s two biggest concerns are the health of Torii Hunter and the development of catcher Joe Mauer. This will be a competitive club, but they lack in power. Pitching will keep this team in contention for the majority of the year, but it remains to be seen how this team will put runs on the board. Jacque Jones’s departure leaves the middle of the Minnesota lineup thin.

Detroit Tigers: Placido Polanco will have a good year, and should be a good player for quite some time. Pudge Rodriguez is doing his best to be a leader and producer. The Tigers are showing signs of life, but they are still several years and players away. Magglio Ordonez is looking to rebound from an injury shortened ’05 campaign, and should put up numbers if he is able to shake the injury bug. Kenny Rogers will eat up innings, and possibly mentor the rest of the young Tigers’ staff. The Ugueth Urbina “Machete Madness Party” left a hole where the bullpen used to be, and there isn’t anything this team can do to finish better than fourth in the Central.

Kansas City Royals: Pitcher Zack Greinke briefly left spring training “for personal reasons.” Can’t say the thought of running away from the Royals wouldn’t cross our minds. When the prize free agency signing your franchise touts is the fossilized remains of Reggie Sanders, you know the win total is going to be in the 70s. Young talent on the roster will leave town as soon as possible. There really isn’t much to say about this franchise and competitive baseball unless you want to take it back to the days of their pale blue jerseys and cassette tapes.

AL WEST

Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim: The tandem of Vladimir Guerrero and Bartolo Colon alone should be enough to secure another division title. Last year’s divisional champs lost some veteran talent but have correctly assessed that room had to be made for their talented farmhands Jeff Mathis, Dallas Macpherson and Casey Kotchman. Chone Figgins is one of the most underrated players in the league. He’s like Jose Oquendo with top-flight skills.

Oakland Athletics: We’re rooting for Frank Thomas to stay healthy and hit 40 home runs. Expect big seasons from pitchers Rich Harden and Danny Haren, but also expect Barry Zito to be elsewhere at the All-Star break. Huston Street is one of the most exciting young closers in the league, and this staff should be able to get the ball into his hands often enough. But where are the outfield bats? Shortstop Bobby Crosby’s health is also a significant issue. If this team does eke out a wild-card berth, they will be bounced from the first round.

Texas Rangers: Runs are going to be scored. In bunches. Kevin Millwood should replace Kenny Rogers just fine. He’ll probably be better received by cameramen as well. Hank Blalock and Mark Texiera will launch dozens upon dozens of homeruns, but it’s going to be more of the same in Arlington. Until Texas gets more quality starts from their staff, they aren’t going to return to postseason play. If they can keep their tandem of young sluggers under contract and bring in some midlevel pitching they will be able to contend in a few years.

Seattle Mariners: No matter what sort of offensive production new catcher Kenji Johjima provides, the language gap with the pitching staff is going to take a toll over the duration of the season. Richie Sexson and Adrian Beltre will probably have solid years, and so will Ichiro, but the sinew in the batting order just isn’t there anymore. When Seattle was very successful, they had guys like Jay Buhner to serve as support to the bigger talents in the lineup. For the kind of ballpark Safeco is, this team’s composition isn’t a dreamy match. Jamie Moyer will squeeze another year out of his aging body, but this team is going to have to wallow in the cellar for a few years with what they have.

NL EAST

New York Mets: It comes down in large part to the Carloses. If Delgado stays healthy and Beltran has a better year, this team will end the Braves’ endless string of NL East titles. We’ll hear more than enough about Pedro Martinez’s toe. The addition of Billy Wagner gives the Mets their most reliable closer since Randy Myers. Expectations and the payroll are high, but this is the year for the Mets to shine. Infielders Jose Reyes and David Wright will improve both at the bat and in the field. New catcher Paul Lo Duca will throw out some runners. And middle relief, until some brilliant offseason moves the team’s weak spot, will prove to be the league’s best.

Atlanta Braves: The song remains the same. The roster changes yearly, yet Bobby Cox gets the most out of what he has. Jeff Francoeur continues to emerge as one of the best right fielders in the game. It remains to be seen if Edgar Renteria will be the All Star he was as a Cardinal, or the error machine he was while with the Red Sox. John Smoltz and Tim Hudson are as good as any front end of a rotation. Unfortunately for Atlanta, New York’s offense is far superior.

Philadelphia Phillies: Ryan Howard is as impressive a young slugger as you will find in the game today. Jimmy Rollins will continue his solid play though not his 2005 batting streak. We’ll see if all the trade rumors affect Bobby Abreu, and watch as their marginal pitching staff keeps them from excelling. Tom Gordon closing might not work out so well either.

Washington Nationals: The combustive personalities of Jose Guillen and Alfonso Soriano in one clubhouse does not bode well for team chemistry, or high numbers in the win column. Cristian Guzman is the new Rey Ordonez. Livan Hernandez is counted on to be the ace, again, and to throw too many innings, again. This squad overachieved last year, but their true colors (and paltry offense) will show. You’ll hear more about off-the-field bickering than you will about anything else. Unless it’s the trade of Soriano or Jose Vidro to the Mets...

Florida Marlins: Joe Girardi sure fell for the ol’ bait-and-switch on this one. After the ex-Yank was hired as manager, the systematic dissolution of the team began. It is highly likely that Dontrelle Willis and Miguel Cabrera will be moved. No one wants to sit in the Miami sun or evening murk to watch a game. Even though this team has won two world championships recently, they are dead in the water. Until an ownership group steps up and moves this team, it’s going to be all bad. At the rate this team is being scrapped, Girardi might find himself catching by the end of the year.

NL CENTRAL

St. Louis Cardinals: This team is good enough to contend in any division, but since they’re in the oh-so-weak Central it’s going to be a cakewalk. Expect St. Louis to win the division by more than a dozen games. Albert Pujols is one of the three best players in the league, and there isn’t going to be anyone breathing down this club’s neck much past the All Star break. It’s really too bad that the Cardinals are always ho-humming by the time the playoffs roll around, because in the era of the wild card, momentum in September means a lot to how a team plays in October.

Houston Astros: As NASA would say, the window has closed. The Roger Clemens experience is over, as is Jeff Bagwell’s career. This team might contend for a wild card, but if Andy Pettite gets hurt it’s over. Willy Taveras is an exciting player who should continue to develop. Count on Brad Lidge to bounce back from his playoff blowup. The addition of Preston Wilson isn’t going to put this team over the top.

Milwaukee Brewers: As their superb young talent continues to develop, their record will improve. If you’re looking for a Cinderella (or George Mason) story, you could do worse than picking the Brew Crew to take the wild card. Prince Fielder and Richie Weeks are going to be perennial All Stars. However, if the race for the playoffs is tight in September, count on the Astros to prevail this year.

Chicago Cubs: Dusty Baker’s head is going to roll this summer. The Chicago media has been calling for it for years, and the expected injuries to Kerry Wood and Mark Prior are going to make the axe fall. The White Sox winning the Series last year didn’t exactly appease Cubs fans’ desire to win one. As long as this club’s success is tied to the balky bodies of their two young aces, the drought will continue.

Cincinnati Reds: Eric Milton may be the worst starting pitcher in baseball. Expect him to challenge Bert Blyleven’s record for most homers surrendered in a year, while doubling Blyleven’s ERA. New ownership may right this ship eventually, but it’s not a one year plan. The pitching staff is laughable, even with the acquisition of Bronson Arroyo. Combine the sketchiness of the rotation with their outfielders’ inability to stay healthy, and the result is another year of high-scoring losses. This club reminds one of the 1930 Phillies.

Pittsburgh Pirates: Ouch is all you can say when looking at this team. Anything short of time warping and bringing back a young Barry Bonds or Willie Stargell just won’t do. Jason Bay is a solid player, but teams on which Joe Randa is an Opening Day starter do not fare well. Suggested trade: swap entire roster for that of the Tampa Bay Devil Rays and see whether playing in a decent home ballpark makes a difference.

NL WEST

San Diego Padres: Mike Cameron deserves to play center field again, and The City Where the Weather Never Changes should make for a nice change from New York. The fates would have it for him to do so at the same field where he nearly ended his baseball career last summer. Mike Piazza finally is free of expectations, and should do well as the marquee player on his new club. This is a division which can be won by a team with a losing record. If San Diego played in a different division, they might struggle to make the postseason. In the NL West, an 85-win team is king.

Los Angeles Dodgers: Kenny Lofton will be old enough to get a 15% discount at IHOP by the end of the year, so having him start in center field might not be the best plan. We’re rooting for Nomar Garciaparra to resurrect his career in LA while learning how to play first base. Safest prediction in the bunch: Jeff Kent will fight someone in Dodger blue. If J.D. Drew plays more than 145 games this year confetti should drop from the sky. Ever since the team acquired Darryl Strawberry, clubhouse chemistry has been rocky or nonexistent.

San Francisco Giants: Barry Bonds could hit 10 or 60 home runs this year, but he can’t pitch while doing it. Omar Vizquel, Steve Finley and the rest of the over-the-hill gang can not protect Bonds in the lineup (assuming he can even play). This year will be nothing but an orgy of media attention focused on Barry’s off-the-field issues, and that can’t help the team.

Arizona Diamondbacks: There isn’t a lot of good going on in Arizona right now. Orlando Hudson looks to have a bounce-back year, but this team is pretty devoid of upcoming talent. Names like Shawn Green and Luis Gonzalez look good on paper, but there’s not much left in their tanks.

Colorado Rockies: Another expansion debacle, this team will likely never be competitive. With the altitude induced long balls, the demoralized pitching staff this team will resemble a backyard Whiffle ball squad more than a major league one. Rockies pitchers show their stuff before they get here and after they leave. One wonders what kind of numbers Todd Helton would put up if he didn’t play in Colorado. One wonders whether the league will allow a special dead ball to be used in Rockies home games. One also wonders if this team will win 70 games.

DIVISIONAL PLAYOFFS: Mets over Astros

DIVISIONAL PLAYOFFS: Cardinals over Padres

NLCS: Mets over Cardinals

DIVISIONAL PLAYOFFS: Angels over Red Sox

DIVISIONAL PLAYOFFS: Yankees over White Sox

ALCS: Angels over Yankees

WORLD SERIES: Mets over Angels in 6

--Isaac Thorn and John Thorn

Saturday, March 25, 2006

The Antigone Complex

By Mark Thorn:

In formulating his theory of the Oedipus complex, Freud first noticed a parallel between a theme in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex and the attitudes children commonly hold toward their parents—intense love for the parent of the opposite sex and jealousy of and hostility toward the parent of the same sex. Freud thus interpreted Oedipus’ unwitting perpetration of patricide and mother-incest as the fulfillment of the unconscious wish among all boys to replace their fathers as the love-objects of their mothers.[1] One of Oedipus’ two daughters, Antigone, also inspired a Sophoclean play which bears her name, seemingly a tale of a young woman’s defiance of civil law in favor of a higher moral law. As we will see, however, the events of Antigone’s life, including her purportedly moral burial of her brother, Polyneices, represent normal stages of the evolution of the female psyche.

The play opens with conversation between Antigone and Ismene, the daughters of Oedipus, regarding the dishonorable mortuary treatment of their recently deceased brother, Polyneices. Antigone decides to perform for Polyneices proper burial rites and in so doing violate a prohibition of Creon, the king of Thebes. Around this premise the plot unfolds, resulting ultimately in the suicides of Antigone and Creon’s wife and son. Though Antigone is superficially a moralizing play, as it implicitly advises its audience to adhere to internal rather than imposed morals, its true psychological significance emerges only in the context of the entire Oedipus legend. Only upon analyzing the events of Antigone’s life which preceded the action of Antigone will her moral obstinacy become comprehensible.

Early in her life Antigone suffered the loss of her mother and the utter debilitation of her father. As the only willing candidate, she tended to her blind father for the many years before his death. Her sexual inexperience, to which the dialogue of Antigone often refers, seemed unavoidable, as she was occupied constantly by the needs of her father. Antigone’s careful treatment of her father, however, admits of a symbolic interpretation which sheds light upon the subsequent events of her life.

According to Freud, as the mother is the first love-object of the little boy, the father is the first love-object of the little girl.[2] The little girl is envious of the affection which the mother displays toward the father and wishes that instead she were the one to whom the father looked for care. Perhaps then, Oedipus, the ostensible obstacle to Antigone’s love life, in reality composed the whole of Antigone’s love life; Antigone had in fact succeeded in replacing her mother as the caretaker of her father, thereby fulfilling the primary sexual wish of the female unconscious.

One may here object that Antigone was forced to assume the role of Oedipus’ caretaker by external circumstance—that Antigone’s situation was a product of the inadvertent misdeeds of Oedipus, his subsequent self-blinding, and the suicide of Jocasta, in all of which Antigone played no part. This apparent predetermination of the course of Antigone’s life, however, provides no contradiction to our assertion that her tending to Oedipus reflects the little girl’s wish to replace the mother. Oedipus’ crimes were similarly fated, yet Freud devised an ingenious explanation for the seeming predetermination: Oedipus’ ignorance of his misdeeds represents the unconscious nature of the little boy’s desires; the little boy has an inherent, perhaps fated tendency, as did Oedipus, to desire the position of the father. And as the course of Antigone’s life, like that of Oedipus, represents the realization of unconscious wishes, it is unreasonable that the fulfillment of those wishes could be attained through conscious action.

At the outset of Antigone, her father now dead, Antigone devotes herself to the proscribed burial of her recently deceased brother, Polyneices. Though a manifestly moral endeavor, her wish to bury her brother also was rooted in primitive unconscious drives.

Freud observed that the little girl’s primary love for the father, invariably fruitless, is often deflected upon a brother: “A little girl finds in her older brother a substitute for her father, who no longer acts towards her with the same affection as in former years.”[3] Thus the irrational zeal with which Antigone pursued the burial of Polyneices represents not familial but sexual love, and Creon’s edict prohibiting the burial of Polyneices truly symbolized the societal proscription of sibling-incest. Though this seems a valid psychoanalytic inference, one may question the connection between burial and sexual love, which to this point remains obscure.

In Greek mythology—and Sophocles’ Oedipus trilogy is but a dramatization of the Oedipus myth—Earth was an animate being, Gaia. Hence when Ouranos stuffed his newborn children into the Earth, he was literally returning them to the womb of their mother, Gaia; he was essentially undoing their births. Antigone’s wish to bury Polyneices in the Earth may accordingly be considered a symbolic wish to envelop him in a womb, the sexual nature of which is made clear by the psychology of Otto Rank.

In The Trauma of Birth, Rank proposed that the shock of being born leaves indelible impressions upon the human psyche, “that man never gives up the lost happiness of pre-natal life and that he seeks to reestablish this former state, not only in all his cultural strivings, but also in the act of procreation.”[4] Rank views the sexual act as an attempt to restore the primal intra-uterine pleasure—physically direct for the male, physically vicarious for the female. Accordingly, Antigone’s burial of Polyneices, her father-surrogate, may unconsciously signify his entry into her womb and the attainment of the sexual love which she had hoped to receive originally from Oedipus.

After being seized by a sentry at the site of Polyneices’ burial, Antigone is forced to discuss with Creon the nature of her crime. Though he affords her ample opportunities to express remorse or even confusion regarding the illegality of her deed, she obdurately asserts her guilt and, unfearing, even embraces the imminent punishment; she proclaims even that her “husband is to be the Lord of Death.”[5] Creon then sentences Antigone to be immured in a cave but is soon persuaded by Teiresias to liberate her, though not before she hangs herself. The somewhat mysterious suicides of Haemon, Antigone’s prospective husband, and Eurydice, Haemon’s mother and Creon’s wife, follow soon thereafter, leaving only Creon to regret his tragic decision.

As the story progresses, it becomes increasingly apparent that Antigone does not fear but anxiously awaits death. But what compels her to seek death? A closer analysis of her suicide elucidates the unconscious forces at play.

Throughout mythology and dreams, the cave frequently symbolizes the womb. Therefore hanging in a cave, as Antigone does, symbolizes inhabiting a womb, in which one hangs by the umbilical cord. So perhaps Antigone’s evident wish for death was in fact a wish for a pre-birth state, a desire encompassed in Thanatos, Freud’s death instinct.

Freud supposed that human life was motivated by two fundamental drives: Eros, the life instinct, and Thanatos, the death instinct. While Eros seeks proliferation and activity, Thanatos seeks homeostasis and inactivity; the Death instinct strives toward nonexistence, the state preceding birth. But why was Antigone so anxious to meet death, or rather return to pre-birth? Why was her life governed by Thanatos? Could returning to her mother’s womb satisfy either her primary love for her father or her secondary love for Polyneices, her father-substitute?

Gestation, the period of primal pleasure, is the predecessor to coitus. Hence by returning to the symbolic womb of her mother in which she, Polyneices, and Oedipus were conceived, she at last achieves the intimate union with Oedipus and Polyneices which she had so long desired. Antigone unconsciously experiences a pleasure with her father and brother beyond that of sexual intercourse, for gestation is the primary experience from which sex derives its secondary pleasurable character.

The discovery of Antigone’s dead body is followed immediately by the suicides of Haemon and Eurydice. Though these subsequent deaths contribute to the play’s tragic effect, they seem utterly impulsive, perhaps even gratuitous. Are these deaths affective simply because of their shocking nature or do they symbolically enhance the scene of Antigone’s suicide?

In answer, first we are tempted to pursue the obvious parallels between Haemon and Polyneices; they were both sons of kings, and Haemon loved Antigone as she loved Polyneices. Thus the death of Haemon, a practical Polyneices-surrogate, beside Antigone incarnates her unconscious reunification with her brother, the Oedipus-surrogate. Similarly, Eurydice and Jocasta are analogous characters; both women were the wives of kings, and Eurydice birthed Haemon, the Polyneices-substitute. Consequently Eurydice’s suicide beside Haemon and Antigone emphasizes the cave’s symbolic significance as Jocasta’s womb.

Although we have outlined already how the pleasures of pre-birth and coitus are associated with burial and death, there remains a deeper, more abstract meaning of the play’s series of deaths. Among the men in Antigone’s life, Oedipus is the first to expire, her brothers Polyneices and Eteocles second, and Haemon the last. This sequence is not arbitrary; each successive death represents a phase of female sexuality. A girl’s love is directed first toward her father, then displaced upon familial father-surrogates, such as brothers, and finally deflected upon a seemingly unrelated love-object, such as Haemon. The three male deaths in Antigone then signify the extinction of various stages of female sexuality, the love-object of each a substitute for that of the preceding stage. Antigone, however, hangs herself before displacing her sexual love onto an unrelated object, such as Haemon; any gratification arising from such a relationship, she understands unconsciously, would be merely substitutive and she opts instead for the primal pleasure of the symbolic womb.

One may now object that the correspondence here posited between the events of Antigone’s life and the phases of female sexuality is perhaps applicable only to neurotics if not specious altogether. To this we can respond only that Freud took the same liberty—that of generalizing phenomena among neurotics to healthy individuals—in his interpretation of the Oedipus myth. Furthermore, this essay proposes no amendments of or supplements to psychoanalytic sexual theory; it constitutes only a mythological confirmation of the psychoanalytic theory of female sexuality Freud first established through empirical observation.

“Antigone” literally means “against birth,” or “contrary birth,” which most have interpreted to indicate Antigone’s status as the product of incest, a perverse or “contrary” union.[6] However, a literal interpretation of “against birth” is perhaps more significant. Antigone unconsciously wished to return to the womb, to pre-birth; she truly wished to undo her birth throughout the action of Antigone. Antigone embodies the human predicament: the forced renunciation of primary and secondary love-objects, the subsequent substitute-gratifications, the perpetual conflict between social demands and instinctual aims, and the clash between the two irresolvable fundamental drives—one seeking life and pleasure, the other wishing to undo life altogether.

In formulating his theory of the Oedipus complex, Freud first noticed a parallel between a theme in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex and the attitudes children commonly hold toward their parents—intense love for the parent of the opposite sex and jealousy of and hostility toward the parent of the same sex. Freud thus interpreted Oedipus’ unwitting perpetration of patricide and mother-incest as the fulfillment of the unconscious wish among all boys to replace their fathers as the love-objects of their mothers.[1] One of Oedipus’ two daughters, Antigone, also inspired a Sophoclean play which bears her name, seemingly a tale of a young woman’s defiance of civil law in favor of a higher moral law. As we will see, however, the events of Antigone’s life, including her purportedly moral burial of her brother, Polyneices, represent normal stages of the evolution of the female psyche.

The play opens with conversation between Antigone and Ismene, the daughters of Oedipus, regarding the dishonorable mortuary treatment of their recently deceased brother, Polyneices. Antigone decides to perform for Polyneices proper burial rites and in so doing violate a prohibition of Creon, the king of Thebes. Around this premise the plot unfolds, resulting ultimately in the suicides of Antigone and Creon’s wife and son. Though Antigone is superficially a moralizing play, as it implicitly advises its audience to adhere to internal rather than imposed morals, its true psychological significance emerges only in the context of the entire Oedipus legend. Only upon analyzing the events of Antigone’s life which preceded the action of Antigone will her moral obstinacy become comprehensible.

Early in her life Antigone suffered the loss of her mother and the utter debilitation of her father. As the only willing candidate, she tended to her blind father for the many years before his death. Her sexual inexperience, to which the dialogue of Antigone often refers, seemed unavoidable, as she was occupied constantly by the needs of her father. Antigone’s careful treatment of her father, however, admits of a symbolic interpretation which sheds light upon the subsequent events of her life.

According to Freud, as the mother is the first love-object of the little boy, the father is the first love-object of the little girl.[2] The little girl is envious of the affection which the mother displays toward the father and wishes that instead she were the one to whom the father looked for care. Perhaps then, Oedipus, the ostensible obstacle to Antigone’s love life, in reality composed the whole of Antigone’s love life; Antigone had in fact succeeded in replacing her mother as the caretaker of her father, thereby fulfilling the primary sexual wish of the female unconscious.

One may here object that Antigone was forced to assume the role of Oedipus’ caretaker by external circumstance—that Antigone’s situation was a product of the inadvertent misdeeds of Oedipus, his subsequent self-blinding, and the suicide of Jocasta, in all of which Antigone played no part. This apparent predetermination of the course of Antigone’s life, however, provides no contradiction to our assertion that her tending to Oedipus reflects the little girl’s wish to replace the mother. Oedipus’ crimes were similarly fated, yet Freud devised an ingenious explanation for the seeming predetermination: Oedipus’ ignorance of his misdeeds represents the unconscious nature of the little boy’s desires; the little boy has an inherent, perhaps fated tendency, as did Oedipus, to desire the position of the father. And as the course of Antigone’s life, like that of Oedipus, represents the realization of unconscious wishes, it is unreasonable that the fulfillment of those wishes could be attained through conscious action.

At the outset of Antigone, her father now dead, Antigone devotes herself to the proscribed burial of her recently deceased brother, Polyneices. Though a manifestly moral endeavor, her wish to bury her brother also was rooted in primitive unconscious drives.

Freud observed that the little girl’s primary love for the father, invariably fruitless, is often deflected upon a brother: “A little girl finds in her older brother a substitute for her father, who no longer acts towards her with the same affection as in former years.”[3] Thus the irrational zeal with which Antigone pursued the burial of Polyneices represents not familial but sexual love, and Creon’s edict prohibiting the burial of Polyneices truly symbolized the societal proscription of sibling-incest. Though this seems a valid psychoanalytic inference, one may question the connection between burial and sexual love, which to this point remains obscure.

In Greek mythology—and Sophocles’ Oedipus trilogy is but a dramatization of the Oedipus myth—Earth was an animate being, Gaia. Hence when Ouranos stuffed his newborn children into the Earth, he was literally returning them to the womb of their mother, Gaia; he was essentially undoing their births. Antigone’s wish to bury Polyneices in the Earth may accordingly be considered a symbolic wish to envelop him in a womb, the sexual nature of which is made clear by the psychology of Otto Rank.

In The Trauma of Birth, Rank proposed that the shock of being born leaves indelible impressions upon the human psyche, “that man never gives up the lost happiness of pre-natal life and that he seeks to reestablish this former state, not only in all his cultural strivings, but also in the act of procreation.”[4] Rank views the sexual act as an attempt to restore the primal intra-uterine pleasure—physically direct for the male, physically vicarious for the female. Accordingly, Antigone’s burial of Polyneices, her father-surrogate, may unconsciously signify his entry into her womb and the attainment of the sexual love which she had hoped to receive originally from Oedipus.

After being seized by a sentry at the site of Polyneices’ burial, Antigone is forced to discuss with Creon the nature of her crime. Though he affords her ample opportunities to express remorse or even confusion regarding the illegality of her deed, she obdurately asserts her guilt and, unfearing, even embraces the imminent punishment; she proclaims even that her “husband is to be the Lord of Death.”[5] Creon then sentences Antigone to be immured in a cave but is soon persuaded by Teiresias to liberate her, though not before she hangs herself. The somewhat mysterious suicides of Haemon, Antigone’s prospective husband, and Eurydice, Haemon’s mother and Creon’s wife, follow soon thereafter, leaving only Creon to regret his tragic decision.

As the story progresses, it becomes increasingly apparent that Antigone does not fear but anxiously awaits death. But what compels her to seek death? A closer analysis of her suicide elucidates the unconscious forces at play.

Throughout mythology and dreams, the cave frequently symbolizes the womb. Therefore hanging in a cave, as Antigone does, symbolizes inhabiting a womb, in which one hangs by the umbilical cord. So perhaps Antigone’s evident wish for death was in fact a wish for a pre-birth state, a desire encompassed in Thanatos, Freud’s death instinct.

Freud supposed that human life was motivated by two fundamental drives: Eros, the life instinct, and Thanatos, the death instinct. While Eros seeks proliferation and activity, Thanatos seeks homeostasis and inactivity; the Death instinct strives toward nonexistence, the state preceding birth. But why was Antigone so anxious to meet death, or rather return to pre-birth? Why was her life governed by Thanatos? Could returning to her mother’s womb satisfy either her primary love for her father or her secondary love for Polyneices, her father-substitute?

Gestation, the period of primal pleasure, is the predecessor to coitus. Hence by returning to the symbolic womb of her mother in which she, Polyneices, and Oedipus were conceived, she at last achieves the intimate union with Oedipus and Polyneices which she had so long desired. Antigone unconsciously experiences a pleasure with her father and brother beyond that of sexual intercourse, for gestation is the primary experience from which sex derives its secondary pleasurable character.

The discovery of Antigone’s dead body is followed immediately by the suicides of Haemon and Eurydice. Though these subsequent deaths contribute to the play’s tragic effect, they seem utterly impulsive, perhaps even gratuitous. Are these deaths affective simply because of their shocking nature or do they symbolically enhance the scene of Antigone’s suicide?

In answer, first we are tempted to pursue the obvious parallels between Haemon and Polyneices; they were both sons of kings, and Haemon loved Antigone as she loved Polyneices. Thus the death of Haemon, a practical Polyneices-surrogate, beside Antigone incarnates her unconscious reunification with her brother, the Oedipus-surrogate. Similarly, Eurydice and Jocasta are analogous characters; both women were the wives of kings, and Eurydice birthed Haemon, the Polyneices-substitute. Consequently Eurydice’s suicide beside Haemon and Antigone emphasizes the cave’s symbolic significance as Jocasta’s womb.

Although we have outlined already how the pleasures of pre-birth and coitus are associated with burial and death, there remains a deeper, more abstract meaning of the play’s series of deaths. Among the men in Antigone’s life, Oedipus is the first to expire, her brothers Polyneices and Eteocles second, and Haemon the last. This sequence is not arbitrary; each successive death represents a phase of female sexuality. A girl’s love is directed first toward her father, then displaced upon familial father-surrogates, such as brothers, and finally deflected upon a seemingly unrelated love-object, such as Haemon. The three male deaths in Antigone then signify the extinction of various stages of female sexuality, the love-object of each a substitute for that of the preceding stage. Antigone, however, hangs herself before displacing her sexual love onto an unrelated object, such as Haemon; any gratification arising from such a relationship, she understands unconsciously, would be merely substitutive and she opts instead for the primal pleasure of the symbolic womb.

One may now object that the correspondence here posited between the events of Antigone’s life and the phases of female sexuality is perhaps applicable only to neurotics if not specious altogether. To this we can respond only that Freud took the same liberty—that of generalizing phenomena among neurotics to healthy individuals—in his interpretation of the Oedipus myth. Furthermore, this essay proposes no amendments of or supplements to psychoanalytic sexual theory; it constitutes only a mythological confirmation of the psychoanalytic theory of female sexuality Freud first established through empirical observation.

“Antigone” literally means “against birth,” or “contrary birth,” which most have interpreted to indicate Antigone’s status as the product of incest, a perverse or “contrary” union.[6] However, a literal interpretation of “against birth” is perhaps more significant. Antigone unconsciously wished to return to the womb, to pre-birth; she truly wished to undo her birth throughout the action of Antigone. Antigone embodies the human predicament: the forced renunciation of primary and secondary love-objects, the subsequent substitute-gratifications, the perpetual conflict between social demands and instinctual aims, and the clash between the two irresolvable fundamental drives—one seeking life and pleasure, the other wishing to undo life altogether.

--Mark Thorn

[1] Sigmund Freud. James Strachey, ed., The Interpretation of Dreams, 1st ed. (New York: Basic Books, 1955) 261, Questia, 3 Mar. 2006 http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=99556184.

[2] Sigmund Freud, A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis., trans. G. Stanley Hall (New York: Horace Liveright, 1920) 288, Questia, 3 Mar. 2006 http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=102189529.

[3] Sigmund Freud, A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis., trans. G. Stanley Hall (New York: Horace Liveright, 1920) 289, Questia, 8 Mar. 2006 http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=102189530.

[4] Alexander Franz. (1925). M.S.Bergmann & F.R.Hartman (eds.). The Evolution of Psychoanalytic Technique (pp. 107). New York: Columbia University Press 1990.

[5] Sophocles. Sophocles I. 2nd ed. (pp. 193). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

[6] Campbell, Mike. "Antigone." Behind the Name. 03 Mar. 2006 http://www.behindthename.com/php/view.php?name=antigone.

[5] Sophocles. Sophocles I. 2nd ed. (pp. 193). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

[6] Campbell, Mike. "Antigone." Behind the Name. 03 Mar. 2006 http://www.behindthename.com/php/view.php?name=antigone.

WORKS CITED

Alexander Franz. (1925). M.S.Bergmann & F.R.Hartman (eds.). The Evolution of Psychoanalytic Technique (pp.99-109). New York: Columbia University Press 1990.

Brazier, Dharmavidya D. "Separation Psychotherapy." Amida Trust. 1992. 02 Mar. 2006

Campbell, Mike. "Antigone." Behind the Name. 03 Mar. 2006

Freud, Sigmund. A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis.. Trans. G. Stanley Hall. New York: Horace Liveright, 1920. Questia. 8 Mar. 2006

Freud, Sigmund. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Trans. James Strachey. Ed. James Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton, 1961. Questia. 8 Mar. 2006

Freud, Sigmund. Strachey, James, ed. The Interpretation of Dreams. 1st ed. New York: Basic Books, 1955. Questia. 8 Mar. 2006

Hesiod. Works & Days, Theogony. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1993.

Rank, Otto. The Trauma of Birth. New York: Robert Brunner, 1952.

Sophocles. Sophocles I. 2nd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Friday, March 24, 2006

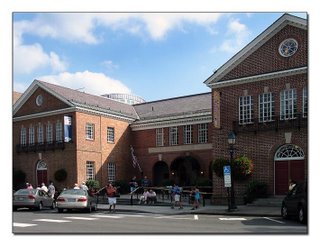

The Road to Cooperstown

From "Play's the Thing," Woodstock Times, March 16, 2006:

So you think you know baseball? If you can answer these questions correctly, you just might make it to the Hall of Fame. Start with the Little League and advance through the ranks to the minors, the majors and, if you've really got what it takes, the World Series. Get the bonus question right, and you may get a call from Cooperstown!

Like Ulysses on his twenty-year journey from home to distant outposts and home again, beware of pitfalls — a midseason trade from a pennant contender to a cellar-dwelling club; that ground ball rolling between your legs; that ill-fated attempt to steal. But even if you're getting splinters in your seat from weeks of bench-warming, one swing of the bat may be all that stands between you and triumph. So ... let's set off for first base.

1. The great American institution started by Abner Doubleday was:

The Civil War. Go to 22.

Baseball. Go to 18.

2. Fans surely benefited from the practice, but an umpire's realm is confined to the field of play. See 25.

3. Which President of the United States played professional baseball?

Dwight D. Eisenhower. Go to 12.

Harry S. Truman. Go to 20.

4. You may have been thinking of a scenario like this: three singles load the bases. The runner on third is caught attempting to steal home. Then, another runner attempts to steal; he is caught, too. Two more singles reload the bases before the third out. Good guess, but not good enough. See 54.

5. Number 1 is a skinny number, a little number, but a wrong number. See 60.

6. Right. Although Stockton, California continues to stake a claim to being the poet's inspiration for Mudville, creator Ernest Lawrence Thayer insisted from the poem's debut in 1888 that Mudville and Casey had no counterparts in real life. Literary sensibilities like yours will be a big plus for the college nine. Go to 61.

7. Which of these rookie prospects signed with a big league organization for the bigger bonus?

Mickey Mantle. Go to 62.

Mario Cuomo. Go to 52.

8. Incredibly early, but true. Only eleven months after Thomas Edison created the incandescent bulb, teams representing two Boston department stores — Jordan Marsh and R.H. White — played a nine-inning night game at Nantasket Beach, concluding in a 16-16 tie. Your first big-league paycheck is in your locker; party on. Go to 48.

9. Here is a little-known lyric from one of baseball's best-loved ballads: “Katie Casey was baseball mad,/ Had the fever and had it bad.” Which one?

Casey at the Bat. Go to 56.

Take Me Out to the Ball Game. Go to 28.

10. Amazing but true! The architects of this “Eighth Wonder of the World” planted natural grass, believing that the sun shining through the glass panels of baseball's first enclosed stadium would provide plenty of light for grass to grow. It did — but the players could not see fly balls against the glare. So, the panels were painted over to protect life and limb ... but then the grass died. To the rescue (and to the continued muttering of fans) came Monsanto Corporation's synthetic Astroturf, installed for the following season. High fives — you've just been signed to a pro contract! Go to 7.

11. A screwball is:

A “reverse curveball” that breaks in the same direction as the throwing arm of the pitcher. Go to 36.

A floating pitch with little if any rotation and an extremely erratic movement. Go to 47.

12. Ike played a season of pro ball before he went to West Point and later played minor-league ball in the Kansas State League under the assumed name of Wilson. In later years he wrote: “A friend of mine and I went fishing and as we sat there in the warmth of a summer afternoon on a river bank we talked about what we wanted to do when we grew up. I told him I wanted to be a real major league baseball player, a genuine professional like Honus Wagner. My friend said that he'd like to be President of the United States. Neither of us got our wish.” You get yours on Opening Day of your next season — playing centerfield and batting leadoff. Go to 45.

13. On April 25, 1901, the Detroit Tigers took the home field in their first game as a major league club in the new American League. Falling steadily behind to the visiting Milwaukee club, the Tigers entered the final frame trailing 13-4. Improbably, they scored ten runs to win their very first game, by a score of 14-13. Perhaps even more improbably, not even a month later, Cleveland duplicated the feat against Washington, also winning 14-13. Nothing like it had ever been done since ... until your club lost the first three games of the World Series and overcame a ten-run deficit in the final inning of Game Seven! (You, of course, capped the rally with a grand-slam homer, Homer.) Now try your hand at the bonus question at the end ... no matter how well (or otherwise) you've done up till now, you may get that call to Cooperstown after all.

14. Wear a scarlet “A,” for your answer is amiss. See 39.

15. The Great Depression slashed attendance throughout baseball by one-third. But the woebegone Browns of 1935 drew only 80,922 paying customers all season long, an 89 percent decline from their peak in the prior decade. But are you depressed? Nah. You got a hit in your first big-league at bat! Go to 31.

16. Maybe Hollywood's Andy Hardy gave rise to Joe Hardy, hero of Damn Yankees, but not to the hero of Casey Stengel's Yankees. See 32.

17. How many times have opposing pitchers in a game each thrown a no-hitter through nine innings?

Once. Go to 49.

Never. Go to 29.

18. Shame on you. You probably believe in Santa Claus, too. Try No. 1 again.

19. Who was the first African American to play major league baseball?

Jackie Robinson. Go to 42.

Moses Fleetwood Walker. Go to 38.

20. No. The pride of Hannibal, Mo., loved baseball and played it as a boy, but his eyesight wasn't good enough to allow him to compete ... so he served as umpire! See 12.

21. When the St. Louis Browns' showman owner Bill Veeck signed a 3’7” man named Eddie Gaedel to his team, what number did little Gaedel wear when he came to bat in a 1951 game against Detroit?

"1." Go to 5.

"1/8." Go to 60.

22. Yes indeed. Doubleday ordered the first shot in response to the Confederate assault on Fort Sumter. There is no credible evidence that he had anything to do with baseball, or that it was “invented” in Cooperstown, New York. Congratulations on your proper skepticism. Go to 27.

23. Lynn played Salem under the lights in ’27, but the correct answer dates back far earlier. See 8.

24. Baseball players first wore gathered pants, or knickers, in the 1860s because:

Players could run faster than in trousers. Go to 40.

Players could show off their manly calves and display colorful stockings. Go to 50.

25. True, as baseball lore has it ... although some scholars dispute this. William Ellsworth Hoy was known to one and all, with the directness and insensitivity that characterized the age, as “Dummy.” The 5’4” outfielder was a deaf-mute who, despite his impairment, played with distinction in the major leagues for fourteen seasons. Born in 1862, he threw out the first ball of Game 3 of the World Series in 1961! Let that be a model to you, callow rookie. Go to 11.

26. Logical and true. When a headline writer informs us that Gilhooley has notched his 14th victory or the Mariners have scored three on Chapman's homer, he is unknowingly memorializing one of the most ancient aspects of the national pastime. And for your extraordinary perspicacity and dogged sleuthing, you are hereby proclaimed a baseball archaeologist extraordinaire and entitled to a trip to Cooperstown. At the ticket window, mention that you have completed this Odyssey Around the Bases, pay the full admission charge, and you will surely be granted entrance to the hallowed Hall of Fame.

27. Which has the greater diameter?

The bat. Go to 44.

The ball. Go to 34.

28. “Katie Casey was baseball mad,

Had the fever and had it bad.

Just to root for the hometown crew,

Ev'ry sou, Katie blew.

On a Saturday, her young beau

Called to see if she'd like to go,

To see a show but Miss Kate said, ‘No,

I'll tell you what you can do...’”

The rest you clearly know. On to the varsity nine! Go to 33.

29. O ye of little faith! See 49.

30. Alas, no. But even if you tripped on this puzzler, it still ain’t over. See 13.

31. In the nineteenth century, home plate umpires began using hand signals in addition to shouting out balls and strikes so that:

Fans in the distant stands could keep track of the count. Go to 2.

A deaf batter could keep track of the count. Go to 25.

32. Yup. And Mickey Mantle has often breathed a sigh of relief that his dad gave him Cochrane's nickname instead of his given name ... Gordon. You have just gone 4-for-4 in the final game of the season, with a pair of dingers; your appreciative teammates have given you a nickname — Homer. Go to 3.

33. When mighty Casey struck out, there was no joy in:

Melville. Go to 58.

Mudville. Go to 6.

34. Your eye is keen. The maximum width of the bat is 2.75 inches, while the maximum diameter of the ball is 2.95 inches--a difference of only 2/10 of an inch. You're not in Little League any longer. Go to 9.

35. On Opening Day 1993, the Colorado Rockies made their debut at Mile High Stadium before 80,227 fans. Add 695 and get the St. Louis Browns' 1935 attendance for:

A homestand (20 games). Go to 57.

A full season (at that time, 77 home games). Go to 15.

36. Yes. Generally employed to fade away from batters rather than drift in toward them, a screwball thrown by righthanders like Christy Mathewson would be employed against lefthanded batters, while a lefthander like Carl Hubbell or Tug McGraw would use the pitch against righthanded batters. In your freshman efforts, are you finding the screwball no easier to hit than to define? Go to 53.

37. No. It's a trick question, sure, but who said we couldn't have some fun just like you? See 51.

38. Right. Jackie Robinson broke the big-league color line in 1947, the first time within the memory of almost everyone in baseball. But in 1884, Walker played for Toledo when it was a major league franchise. The majors are not far away for you, either. Go to 21.

39. Yes ... though Leaves of Grass was not a position paper on the evils of Astroturf. Whitman was a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle, covering the exploits of that city's famed Atlantic Base Ball Club in the mid-1850s. As early as 1846 he reported in the Eagle: “In our sun-down perambulations of late, through the outer parts of Brooklyn, we have observed several parties of youngsters playing ‘base,’ a certain game of ball....” A Whitman you're not, but the hometown paper assigns you a ghostwriter and gives you a daily column. Go to 24.

40. This is the conventional explanation, but it defies logic: simply reflect on how players today stretch their leggings almost to their shoetops. See 50.

41. Who has the highest lifetime batting average in baseball history of men who played in at least 500 games?

Ty Cobb. Go to 37.

Mike Stanton. Go to 51.

42. Half right, and thus wrong. See 38.

43. Close, but no cigar. The original rules did require that 21 runs be scored for a victory (the nine-inning rule came later), but that's beside the point. See 26.

44. Look again. See 34.

45. Henry Chadwick, the game's most prominent early writer, began covering the game around 1856. Which of these masters of American literature preceded him as a baseball reporter?

Nathaniel Hawthorne. Go to 14.

Walt Whitman. Go to 39.

46. Reasonable guess, but you're one year too early. See 10.

47. This would describe a knuckleball pretty well. See 36.

48. When Mickey Mantle was born in 1951, his father named him in honor of his own boyhood hero. Which one?

Mickey Rooney. Go to 16.

Mickey Cochrane. Go to 32.

49. Each time a pitcher takes the mound to start a big-league game, he has roughly a one-in-a-thousand chance of throwing a no-hitter. Accordingly, the odds against a double no-hit game are two in a million, but it has happened. On May 2, 1917, Fred Toney of the Cincinnati Reds and Hippo Vaughn of the Chicago Cubs matched no-hitters until the tenth inning, when the unfortunate Vaughn allowed two hits and lost the game. You are luckier — a late-season call-up gets you off those bush-league buses. Go to 35.

50. Harry Wright, manager of the pioneer professional team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, was determined to make his new business pay. Like other promoters before and since, he put a dollar sign on the muscle. It's midseason, you're hitting .380, you've got a fan club ... all's right with the world. Go to 55.

51. Schoolboys know that Ty Cobb batted .366 over his long career to earn his plaque in the Hall of Fame. But relief pitcher Mike Stanton hit .400 (8 hits in 20 at bats), through the end of the 2005 season. (With his next hitless at bat, however, he will slip below the .397 mark of Terry Forster — 31 hits in 78 at bats.) But you knew that, because as your team breezed to its spot in the World Series, you've had plenty of time to study. Go to 59.

52. The former governor of New York, an outfielder for St. John's University, was given a signing bonus of $2,000, a lot of money in 1951. At the end of his first year in the Pittsburgh Pirates chain, he was beaned; thereafter politics looked good to him. Mickey Mantle got $1,100. He went to the Hall of Fame. Maybe you will too. Go to 19.

53. Major League Baseball's first night game was played in Cincinnati in 1935. But when was the first nocturnal attempt to play the national pastime?

1927. Go to 23.

1880. Go to 8.

54. Right. It can happen like this: three singles load the bases. Then the next batter lines a ball that hits a baserunner, producing an out for the team. However, according to the rules, a hit is credited to the batter, who goes to first base. Each of the next two batters produces the same outcome (a single and an out). The season is nearing its end, your club is about to clinch the flag, and you're a legitimate candidate for MVP. Go to 41.

55. What is the maximum number of base hits a team can register in an inning without scoring a run?

Five. Go to 4.

Six. Go to 54.

56. Like Casey, you have taken Strike One. See 28.

57. An average turnout of 4,000 per game would have been cause for rejoicing in St. Louis. See 15.

58. “Call me Casey” is not the opening line of Moby Dick. See 6.

59. It ain’t over ’til it’s over, neither in life nor in that more serious matter, baseball. The greatest single-game comeback — the most runs scored in the bottom of the ninth to win a game — was:

Nine. Go to 30.

Ten. Go to 13.

60. Correct. And the outcome was equally ludicrous. The Detroit pitcher, Bob Cain, almost fell off the mound from laughing and walked Gaedel on four pitches — all of them high! You're hitting .300 and the big club has its eye on you. Go to 17.

61. What kind of grass was installed in Houston's Astrodome when it opened for play in April 1965?

Natural. Go to 10.

Artificial. Go to 46.

62. You would think so, wouldn't you? But scouts make mistakes. See 52.

BONUS. The reason we say that we “keep score” in baseball is:

The earliest rules required a score of runs (a score = 20) for a victory. Go to 43.

The tally keeper notched (scored) a stick with his knife, one for each run. Go to 26.

So you think you know baseball? If you can answer these questions correctly, you just might make it to the Hall of Fame. Start with the Little League and advance through the ranks to the minors, the majors and, if you've really got what it takes, the World Series. Get the bonus question right, and you may get a call from Cooperstown!

Like Ulysses on his twenty-year journey from home to distant outposts and home again, beware of pitfalls — a midseason trade from a pennant contender to a cellar-dwelling club; that ground ball rolling between your legs; that ill-fated attempt to steal. But even if you're getting splinters in your seat from weeks of bench-warming, one swing of the bat may be all that stands between you and triumph. So ... let's set off for first base.

1. The great American institution started by Abner Doubleday was:

The Civil War. Go to 22.

Baseball. Go to 18.

2. Fans surely benefited from the practice, but an umpire's realm is confined to the field of play. See 25.

3. Which President of the United States played professional baseball?

Dwight D. Eisenhower. Go to 12.

Harry S. Truman. Go to 20.

4. You may have been thinking of a scenario like this: three singles load the bases. The runner on third is caught attempting to steal home. Then, another runner attempts to steal; he is caught, too. Two more singles reload the bases before the third out. Good guess, but not good enough. See 54.

5. Number 1 is a skinny number, a little number, but a wrong number. See 60.

6. Right. Although Stockton, California continues to stake a claim to being the poet's inspiration for Mudville, creator Ernest Lawrence Thayer insisted from the poem's debut in 1888 that Mudville and Casey had no counterparts in real life. Literary sensibilities like yours will be a big plus for the college nine. Go to 61.

7. Which of these rookie prospects signed with a big league organization for the bigger bonus?

Mickey Mantle. Go to 62.

Mario Cuomo. Go to 52.

8. Incredibly early, but true. Only eleven months after Thomas Edison created the incandescent bulb, teams representing two Boston department stores — Jordan Marsh and R.H. White — played a nine-inning night game at Nantasket Beach, concluding in a 16-16 tie. Your first big-league paycheck is in your locker; party on. Go to 48.

9. Here is a little-known lyric from one of baseball's best-loved ballads: “Katie Casey was baseball mad,/ Had the fever and had it bad.” Which one?

Casey at the Bat. Go to 56.

Take Me Out to the Ball Game. Go to 28.