Friday, December 30, 2005

Fanfare for a Departed Friend

From "Play's the Thing," Woodstock Times, December 29, 2005:

I have been preoccupied with the idea that fans are players too, as tied in as athletes and owners and media with making spectator sport what it is. Although no one seems willing to put it quite this way, I submit that their devotion has bought fans a stake and a say in the game, in the way that ordinary citizens have a sense of ownership in a landmark building or cultural institution. After all, without their pride of place, what is a museum or an opera company, or a ball club, but just another piece of private property?

Skilled and dedicated players, united by adept management, make for great performance, on the field and in the bottom line. Loyal fans, however, are what make a franchise great, even amid a championship drought of biblical proportions.

What makes for a great fan is more difficult to discern, though character is surely at the heart of the matter. This question has worked on me ever since Barry Halper, the celebrated baseball collector and my longtime friend, died last week at age 66. With less fanfare than accompanies the passing of a utility infielder — the wires noted Barry’s death, but only the Jerusalem Post covered his funeral — baseball lost a giant.

Upon learning of his demise, George Steinbrenner said of Barry, “What a great baseball fan he was. I’ll miss him dearly.” How odd, I thought, that the Yankees’ owner would refer to his minority partner this way. Barry owned about 1 percent of the team and in the early 1990s was briefly involved in its operations; he was a successful businessman in New Jersey; and he was a brilliant trader who in 50 years of high-end collecting amassed a memorabilia trove that, when put up for sale in 1999, yielded nearly $30 million and safeguarded his heirs. But Steinbrenner was absolutely right: what made Barry Halper tick — the central thing about him, really — was that he was a great fan, so great that he left an enduring mark upon the game he loved and has, it says here, a claim upon a place in the Baseball Hall of fame.

Collectors get a bad rap, often enough, for their greed, their secretiveness, their covetousness, their parasitic relationship to players. Seldom noted is their vital role in securing the game’s treasures against the ravages of time and indifference, and in identifying as treasures pop-culture artifacts that museums or halls of fame have tended to scorn. Barry had thousands of items from the game as it was played on the field — historic bats, balls, gloves, and uniforms, thousands of autographs — but he also collected the cards, photographs, posters, packaging, and personal items to which the average fan more readily attaches. Barry collected memories as a lepidopterist pins butterflies to a page.

His tastes and instincts rubbed off on the Hall of Fame, making it today a stronger museum and archive. Before the major part of his collection went up for auction at Sotheby’s in September 1999, when its 2,481 lots realized $21,795,646, the Hall acquired a chunk of his collection through a $7.5 million tithing of Major League Baseball’s thirty teams. For those few days of auction frenzy, the rooms at Sotheby’s (memorialized in a lavish auction catalog) became the best baseball museum in the country, except for those who had been fortunate enough to have wangled an invitation to the basement archive in Barry and Sharon Halper’s Livingston, New Jersey home.

Hundreds of players came over to sample Barry’s curiosities and Sharon’s gourmet cooking (written up in the New York Times, consumed with gusto by Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra, Mickey Mantle and legions more). The guests would autograph the items Barry had prepared for them, sometimes in ways not printable in a family newspaper. DiMaggio even autographed a copy of the first issue of Playboy, its cover and centerfold adorned in the nude by his former wife, Marilyn Monroe — though Barry had to swear that he would not reveal the existence of the item while Joe was alive. A trip to the Halper Shrine was, for these players, a magical mystery tour of a baseball history they knew only dimly if at all. Many out-of-town players would seek return invitations on their next time in New York.

I was lucky enough to visit the Halper home several times over the years, sometimes in connection with photo shoots for publications (Barry never asked for a fee, only an unspecified donation to the St. Barnabas Hospital Burn Treatment Center), other times to discuss his ultimately unrealized dream to create a museum that would keep his collection intact. Bridgeport, Hoboken, and Lower Manhattan venues all seemed promising at one point or another, but ultimately his weakening health forced Barry’s hand. Unable to wait any longer for municipalities or developers to get their acts together, he contracted with Sotheby’s.

Born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1939, the same year that the Hall of Fame opened, Barry began collecting baseball material as a boy, hanging out in the clubhouse of the Newark Bears, the Yankees’ top farm club. His collection came to include over a million baseball cards. You know the famous T-206 Wagner, the million-dollar card? Barry had three. He owned every World Series and All-Star program, an outstanding book collection, and lithographs, photos, and jewelry that were to be found nowhere else.

Sometimes he would acquire material that just looked intriguing, confident that he would be able to gather the underlying stories later on. In this area I was sometimes helpful, either at his home or through back-and-forth sleuthing over the phone or through the mails. While his favorite team was the Yankees, and he could never get enough items featuring Babe Ruth and Mickey Mantle or the team’s other great stars, his pride and joy seemed to me to be the truly ancient artifacts that came his way because of his fame: the original Knickerbocker Constitution booklet of 1848, the cane presented to DeWolf Hopper after the first public performance of “Casey at the Bat,” the shotgun with which Ty Cobb’s mother killed her husband.

Barry owned over a thousand game-worn uniforms, which were housed behind a hidden compartment in a wall and accessed by a James Bondish remote control. At the push of a button an “Old Gold” advertising piece, featuring Babe Ruth, slid down toward the floor revealing a clothing rack much like what you might find in a dry-cleaning store. While he could never acquire an Eppa Rixey uniform to complete his Hall of Fame collection, he had everybody else from 1879 on, including such startling survivors as the uniforms of five Hall of Famers from the 1894 Baltimore Orioles: Willie Keeler, Wilbert Robinson, John McGraw, Hughie Jennings, and Joe Kelley. He had a Cap Anson uniform from 1888, a John Clarkson from 1883, a Pud Galvin from 1879 ... breathtaking to a visitor like me, with an antiquarian bent. Barry had unequaled contacts with former players and especially clubhouse men who, amazingly, had preserved uniforms more than a century old and somehow the stuff just kept coming out of the woodwork ... but only for him.

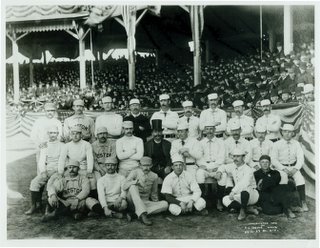

In a move that I later learned was highly unusual — Barry did not like his guests to handle his rarities — I was invited to try on and be photographed in Hoss Radbourn’s Boston Red Stockings road uniform of 1886. This was my reward, perhaps, for having shared with my host the story of a photo that for many years adorned the stairwell leading to his basement. It depicted the Boston Red Stockings and the New York Giants lined up prior to their Opening Day game at the Polo Grounds on April 29, 1886. At the far left in the back row Hoss Radbourn may be detected giving the finger to teammate Sam Wise below him. (Boston center fielder Dick Johnston, born in Kingston, was seated in the bottom row, second from the left.) Barry could barely contain his delight: he now had another story, and that was what, more than anything else, he liked to collect.

Barry was sedate and businesslike unless he got excited by a baseball oddity ... and then he was just a big kid, like all adult fans. Peter Golenbock said of Barry prior to the Sotheby auction, “From early on as he steadfastly accumulated these artifacts with the seriousness of a museum curator, Halper’s primary interest was in their historical or fascination value. He cared little about their worth on resale, because for many years there was no market value. As late as the early 1980s there was no ‘hobby’ as such, only disparate baseball junkies linked by a common interest of owning mementos from the game’s past. The Wall-Streeting of baseball memorabilia would come later.”

“I don’t keep it for the value,” Barry used to say about the motivation behind his collection. “I keep it because I love baseball.”

So love is the “secret” to what makes a great fan? Yes. And it is the secret to greatness on the field and in the front office, where the dollar reigns. Major league players and management are professionals, of course; but what separates the best from the run of the mill is that amateur, loving spirit that spurred them to pursue greatness in the first place, when they were kids.

I have been preoccupied with the idea that fans are players too, as tied in as athletes and owners and media with making spectator sport what it is. Although no one seems willing to put it quite this way, I submit that their devotion has bought fans a stake and a say in the game, in the way that ordinary citizens have a sense of ownership in a landmark building or cultural institution. After all, without their pride of place, what is a museum or an opera company, or a ball club, but just another piece of private property?

Skilled and dedicated players, united by adept management, make for great performance, on the field and in the bottom line. Loyal fans, however, are what make a franchise great, even amid a championship drought of biblical proportions.

What makes for a great fan is more difficult to discern, though character is surely at the heart of the matter. This question has worked on me ever since Barry Halper, the celebrated baseball collector and my longtime friend, died last week at age 66. With less fanfare than accompanies the passing of a utility infielder — the wires noted Barry’s death, but only the Jerusalem Post covered his funeral — baseball lost a giant.

Upon learning of his demise, George Steinbrenner said of Barry, “What a great baseball fan he was. I’ll miss him dearly.” How odd, I thought, that the Yankees’ owner would refer to his minority partner this way. Barry owned about 1 percent of the team and in the early 1990s was briefly involved in its operations; he was a successful businessman in New Jersey; and he was a brilliant trader who in 50 years of high-end collecting amassed a memorabilia trove that, when put up for sale in 1999, yielded nearly $30 million and safeguarded his heirs. But Steinbrenner was absolutely right: what made Barry Halper tick — the central thing about him, really — was that he was a great fan, so great that he left an enduring mark upon the game he loved and has, it says here, a claim upon a place in the Baseball Hall of fame.

Collectors get a bad rap, often enough, for their greed, their secretiveness, their covetousness, their parasitic relationship to players. Seldom noted is their vital role in securing the game’s treasures against the ravages of time and indifference, and in identifying as treasures pop-culture artifacts that museums or halls of fame have tended to scorn. Barry had thousands of items from the game as it was played on the field — historic bats, balls, gloves, and uniforms, thousands of autographs — but he also collected the cards, photographs, posters, packaging, and personal items to which the average fan more readily attaches. Barry collected memories as a lepidopterist pins butterflies to a page.

His tastes and instincts rubbed off on the Hall of Fame, making it today a stronger museum and archive. Before the major part of his collection went up for auction at Sotheby’s in September 1999, when its 2,481 lots realized $21,795,646, the Hall acquired a chunk of his collection through a $7.5 million tithing of Major League Baseball’s thirty teams. For those few days of auction frenzy, the rooms at Sotheby’s (memorialized in a lavish auction catalog) became the best baseball museum in the country, except for those who had been fortunate enough to have wangled an invitation to the basement archive in Barry and Sharon Halper’s Livingston, New Jersey home.

Hundreds of players came over to sample Barry’s curiosities and Sharon’s gourmet cooking (written up in the New York Times, consumed with gusto by Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra, Mickey Mantle and legions more). The guests would autograph the items Barry had prepared for them, sometimes in ways not printable in a family newspaper. DiMaggio even autographed a copy of the first issue of Playboy, its cover and centerfold adorned in the nude by his former wife, Marilyn Monroe — though Barry had to swear that he would not reveal the existence of the item while Joe was alive. A trip to the Halper Shrine was, for these players, a magical mystery tour of a baseball history they knew only dimly if at all. Many out-of-town players would seek return invitations on their next time in New York.

I was lucky enough to visit the Halper home several times over the years, sometimes in connection with photo shoots for publications (Barry never asked for a fee, only an unspecified donation to the St. Barnabas Hospital Burn Treatment Center), other times to discuss his ultimately unrealized dream to create a museum that would keep his collection intact. Bridgeport, Hoboken, and Lower Manhattan venues all seemed promising at one point or another, but ultimately his weakening health forced Barry’s hand. Unable to wait any longer for municipalities or developers to get their acts together, he contracted with Sotheby’s.

Born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1939, the same year that the Hall of Fame opened, Barry began collecting baseball material as a boy, hanging out in the clubhouse of the Newark Bears, the Yankees’ top farm club. His collection came to include over a million baseball cards. You know the famous T-206 Wagner, the million-dollar card? Barry had three. He owned every World Series and All-Star program, an outstanding book collection, and lithographs, photos, and jewelry that were to be found nowhere else.

Sometimes he would acquire material that just looked intriguing, confident that he would be able to gather the underlying stories later on. In this area I was sometimes helpful, either at his home or through back-and-forth sleuthing over the phone or through the mails. While his favorite team was the Yankees, and he could never get enough items featuring Babe Ruth and Mickey Mantle or the team’s other great stars, his pride and joy seemed to me to be the truly ancient artifacts that came his way because of his fame: the original Knickerbocker Constitution booklet of 1848, the cane presented to DeWolf Hopper after the first public performance of “Casey at the Bat,” the shotgun with which Ty Cobb’s mother killed her husband.

Barry owned over a thousand game-worn uniforms, which were housed behind a hidden compartment in a wall and accessed by a James Bondish remote control. At the push of a button an “Old Gold” advertising piece, featuring Babe Ruth, slid down toward the floor revealing a clothing rack much like what you might find in a dry-cleaning store. While he could never acquire an Eppa Rixey uniform to complete his Hall of Fame collection, he had everybody else from 1879 on, including such startling survivors as the uniforms of five Hall of Famers from the 1894 Baltimore Orioles: Willie Keeler, Wilbert Robinson, John McGraw, Hughie Jennings, and Joe Kelley. He had a Cap Anson uniform from 1888, a John Clarkson from 1883, a Pud Galvin from 1879 ... breathtaking to a visitor like me, with an antiquarian bent. Barry had unequaled contacts with former players and especially clubhouse men who, amazingly, had preserved uniforms more than a century old and somehow the stuff just kept coming out of the woodwork ... but only for him.

In a move that I later learned was highly unusual — Barry did not like his guests to handle his rarities — I was invited to try on and be photographed in Hoss Radbourn’s Boston Red Stockings road uniform of 1886. This was my reward, perhaps, for having shared with my host the story of a photo that for many years adorned the stairwell leading to his basement. It depicted the Boston Red Stockings and the New York Giants lined up prior to their Opening Day game at the Polo Grounds on April 29, 1886. At the far left in the back row Hoss Radbourn may be detected giving the finger to teammate Sam Wise below him. (Boston center fielder Dick Johnston, born in Kingston, was seated in the bottom row, second from the left.) Barry could barely contain his delight: he now had another story, and that was what, more than anything else, he liked to collect.

Barry was sedate and businesslike unless he got excited by a baseball oddity ... and then he was just a big kid, like all adult fans. Peter Golenbock said of Barry prior to the Sotheby auction, “From early on as he steadfastly accumulated these artifacts with the seriousness of a museum curator, Halper’s primary interest was in their historical or fascination value. He cared little about their worth on resale, because for many years there was no market value. As late as the early 1980s there was no ‘hobby’ as such, only disparate baseball junkies linked by a common interest of owning mementos from the game’s past. The Wall-Streeting of baseball memorabilia would come later.”

“I don’t keep it for the value,” Barry used to say about the motivation behind his collection. “I keep it because I love baseball.”

So love is the “secret” to what makes a great fan? Yes. And it is the secret to greatness on the field and in the front office, where the dollar reigns. Major league players and management are professionals, of course; but what separates the best from the run of the mill is that amateur, loving spirit that spurred them to pursue greatness in the first place, when they were kids.

--John Thorn

Thursday, December 22, 2005

All I Want for Christmas

From the Saugerties Times, editorial for December 22, 2005:

Dear Santa,

I know I’m a bit tardy with my request, but here it is.

I would like a restoration of our civil liberties for Christmas.

I know it’s big, but I have been mostly good this year. I was going to ask for world peace, but I haven’t been that good.

I understand that you keep an eye on who’s been naughty and nice. I appreciate that. I do think you should know, however, that things are getting crazy down here.

You know about the PATRIOT Act. Yes, that was scary, but it was born of frightening times. People were willing to look the other way as the government trounced all over our rights in the name of Homeland Security.

Now, it turns out, the government has been spying on and monitoring its citizens willy-nilly. The president says it’s to help fight terrorism, but look at some of the groups they’ve been monitoring.

Quakers. The F.B.I. had a group of five Quakers and one grandmother in Lake Worth, Florida under surveillance. Perhaps I take such umbrage because I am a Quaker. I can’t imagine how Quakers could possibly be construed as a terrorist threat. Quakers are pacifists, based on Jesus’s teaching to turn the other cheek and the belief that there is the “Light” in every person. Unless the government fears an outbreak of silent vigils or potluck suppers, I’m hard pressed to think of why Quakers need monitoring. Perhaps it’s to send a message to the Amish and Mennonites.

Vegans. In case you don’t know, these are people who eschew eating or wearing any part of an animal. Basically, they graze in open pastures. I find it hard to believe they’d have the energy to plot anything beyond their next meal. And let’s face it, if someone thinks that animal life is so sacred they will go without decent footwear or a milkshake, I hardly think they’ll be targeting Americans for harm.

Catholic Workers. Again, pacifists. This time, though, they’re Catholic. The F.B.I. described the group as having a “semi-communistic ideology.” Last time I looked, Communists didn’t worship God. Catholic Workers do. In fact, they are moved to a life of simplicity and nonviolence based on their religion. Be afraid. Be very, very afraid.

All of the groups under surveillance -- illegal surveillance, without the benefit of a court-ordered warrant -- were exercising their Constitutional rights. It frightens me to think that in a time when our resources are stretched so thin, with the deficit growing by leaps and bounds, that it is a priority of our government to monitor law-abiding citizens. It reminds me of COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program), the government’s surveillance of activists in the 1960s which, when it came to light in 1975, horrified Americans and led to stronger Congressional oversight of law enforcement.

I’m scared that our government, while ostensibly fighting terrorism, is in fact terrorizing its own citizens. Why are we fighting for democracy in Iraq if democracy in this country is being eroded?

So please, Santa, restore our basic rights. Talk to the President about abiding by the Constitution. Tell him he doesn’t need to live in fear of his own citizens.

And if I promise to be really good next year, could I please have world peace?

--Erica Freudenberger

Dear Santa,

I know I’m a bit tardy with my request, but here it is.

I would like a restoration of our civil liberties for Christmas.

I know it’s big, but I have been mostly good this year. I was going to ask for world peace, but I haven’t been that good.

I understand that you keep an eye on who’s been naughty and nice. I appreciate that. I do think you should know, however, that things are getting crazy down here.

You know about the PATRIOT Act. Yes, that was scary, but it was born of frightening times. People were willing to look the other way as the government trounced all over our rights in the name of Homeland Security.

Now, it turns out, the government has been spying on and monitoring its citizens willy-nilly. The president says it’s to help fight terrorism, but look at some of the groups they’ve been monitoring.

Quakers. The F.B.I. had a group of five Quakers and one grandmother in Lake Worth, Florida under surveillance. Perhaps I take such umbrage because I am a Quaker. I can’t imagine how Quakers could possibly be construed as a terrorist threat. Quakers are pacifists, based on Jesus’s teaching to turn the other cheek and the belief that there is the “Light” in every person. Unless the government fears an outbreak of silent vigils or potluck suppers, I’m hard pressed to think of why Quakers need monitoring. Perhaps it’s to send a message to the Amish and Mennonites.

Vegans. In case you don’t know, these are people who eschew eating or wearing any part of an animal. Basically, they graze in open pastures. I find it hard to believe they’d have the energy to plot anything beyond their next meal. And let’s face it, if someone thinks that animal life is so sacred they will go without decent footwear or a milkshake, I hardly think they’ll be targeting Americans for harm.

Catholic Workers. Again, pacifists. This time, though, they’re Catholic. The F.B.I. described the group as having a “semi-communistic ideology.” Last time I looked, Communists didn’t worship God. Catholic Workers do. In fact, they are moved to a life of simplicity and nonviolence based on their religion. Be afraid. Be very, very afraid.

All of the groups under surveillance -- illegal surveillance, without the benefit of a court-ordered warrant -- were exercising their Constitutional rights. It frightens me to think that in a time when our resources are stretched so thin, with the deficit growing by leaps and bounds, that it is a priority of our government to monitor law-abiding citizens. It reminds me of COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program), the government’s surveillance of activists in the 1960s which, when it came to light in 1975, horrified Americans and led to stronger Congressional oversight of law enforcement.

I’m scared that our government, while ostensibly fighting terrorism, is in fact terrorizing its own citizens. Why are we fighting for democracy in Iraq if democracy in this country is being eroded?

So please, Santa, restore our basic rights. Talk to the President about abiding by the Constitution. Tell him he doesn’t need to live in fear of his own citizens.

And if I promise to be really good next year, could I please have world peace?

--Erica Freudenberger

Friday, December 02, 2005

What's in a Name?

From "Play's the Thing," Woodstock Times, December 1, 2005:

Though still dazed after the annual eating contest that Thanksgiving has become, I kept my eyelids pried open long enough to watch plenty of sports. If you are a New York fan across the four major team sports, this was as exciting a weekend as we’ve had in a long time.

In basketball the Knicks won in overtime on a buzzer-beater by the smallest player on the court, while the Nets won in overtime over the Lakers despite Kobe Bryant’s 46 points. In hockey the Rangers won an overtime shootout that was thrillingly extended to a record fifteen rounds; the Devils and Islanders won weekend games too. The Mets landed free agents first baseman Carlos Delgado and relief pitcher Billy Wagner and now seem plausibly pennant-bound in ’06; the Yankees will close a deal soon and, as always, will assure a way into the playoffs. The Giants rallied in the final minutes to create an overtime scenario, only to kick away three opportunities for a game-winning field goal. Only the Jets lost, but they may be forgiven all in this injury-shattered season, once so rosy.

Jets, Mets, Knicks ... Nets, Devils, Islanders ... Rangers, Giants, Yankees. In a tryptophanic reverie I began to wonder how did New York’s teams come to be known this way? I have written articles previously in this space about why athletes play, why fans root, and how team colors arose. It occured to me that I had created a chair with only three legs, and needed now to talk about how sports teams, mostly in our neighborhood, came by their names. (It would be fun to go far afield to plumb the gunslinger psychology of, say, the Houston Colt .45s, Baltimore Bullets, and St. Louis Bombers, but I have been accorded limited space.)

The oldest of surviving New York sports names is Knickerbocker, attached to the famous baseball club of Alexander Cartwright and his fastidious companions who in 1846 began to play the new game. The Knicks ceased to play competitive baseball in the 1860s and the club disbanded in 1882, but in 1946, a century after they had played the first match game by modern rules, their name was exhumed by a team playing a sport that wasn’t even invented until after the Knicks were gone. Today’s Knicks show no sign of their borrowed heritage in their corporate identity, but their first logo clearly invokes the Old Dutch Patroons of Washington Irving.

Next oldest is — surprise! — the Mets. Their official name of the New York Metropolitan Baseball Club came into being in 1961, the year before they took the field for their inaugural campaign at the old Polo Grounds, haunted with memories of the departed baseball Giants. However, as the Metropolitan Base Ball Club of New York the Mets had provided a major-league entry in 1883-87 and could trace its first incarnation back to 1857. The Jets and Nets were both named to rhyme with Mets, although each was born under another name—the Jets as the Titans (also playing in the Polo Grounds and echoing the Giants), the Nets as the Americans.

Newspapers attached the “Giants” name to the Chicago club also known as the White Stockings (today’s Cubs) in the mid-1880s, but by 1888 it had stuck to New York’s National League entry, which had previously been termed the Gothams, after an amateur club of the Knickerbocker era. When a New York entry came into the National Football League in 1925, it leased the Polo Grounds and took the baseball team’s name. These Giants vacated the Polo Grounds for Yankee Stadium a year before the baseball team hightailed it to San Francisco. Yet even today, local sports announcers call the team “the New York Football Giants,” in apposition to a ghost.

In the early days of major league baseball the press would usually refer to teams by their geographical locators alone: the Bostons would play against the New Yorks, the Detroits against the Chicagos. As some cities acquired additional big league entries, and sports sections began to enlarge, there was a need for short, punchy mascot names: Brown Stockings (“Browns”), Red Stockings (“Reds”), and so on. Brooklyn’s Trolley Dodgers of 1883 (so named because fans crossing from the trolley to the ballpark had to be watchful for cars arriving by intersecting lines) became Superbas and then Dodgers, Robins and, often as not, Bums. The Bums went west to Los Angeles, but when the American Football League began play in 1960, the team placed in L.A. (and long since relocated to San Diego) was called the Chargers because it sort of rhymed with Dodgers.

The Yankees arrived on the scene around 1913, although the team had joined the American League a decade earlier to replace the Orioles of Baltimore. They played as the New Yorks, the Greater New Yorks (referencing the 1898 consolidation of today’s five boroughs into one city), and the Highlanders. This name reflected not only their Hilltop Park in northern Manhattan, overlooking the Hudson River from the site of today’s Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, but also their owner Joseph Gordon. Punning newsmen referenced the Gordon Highlanders, a fabled Scottish fighting regiment.

Actually, the name “Yankees” is more apt for a Boston or New England team, and the NFL fielded a Boston Yankee eleven. If turnabout is fair play, then it is fitting that the home of the Braves (originally in Boston, then in Milwaukee, and since 1966 in Atlanta) derives from New York’s Tammany Hall, whose leader James Gaffney bought the team in 1912.

New York’s first National Hockey League franchise was the Americans, founded in 1925. When boxing promoter and Madison Square Garden president Tex Rickard installed a second team in 1926, fans and sportswriters referred to the new squad as “Tex’s Rangers,” and the name stuck. Staying with hockey for a bit, New Jersey’s Devils were originally the Kansas City Scouts, transplanted to the Pine Barrens and renamed for a Sasquatch-like swamp critter that was said to prowl there. The Islanders name is a prosaic restating of their location on Long Island, while associating with the larger metropolis of New York to which so many Island residents commute for work.

Irksome to me lately has been a baseball attempt to follow in the footsteps of the “Long Island Islanders,” creating a linguistic conundrum with odd resonance. The owner of the team formerly known as the Anaheim Angels (until the 2005 campaign) is Arte Moreno, who has revealed himself to be not only a shrewd businessman but a linguistic strategist of the first order. By renaming his team as the “Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim” he remains in technical, perhaps niggling compliance with the term of his lease with the city stipulating that Anaheim is to be included in the team’s name. By adding “Los Angeles” he intends to surf on the presumed benefits of attaching to a larger metropolitan area, with a presumably more lucrative media profile.

The official team position on the new name is that it honors the team’s roots, for the expansion franchise commenced play in the ballpark of the former Pacific Coast League Los Angeles Angels. But the franchise has been located in Anaheim since 1966. An equivalent “honoring” of a vacated city might be the Brooklyn Dodgers of Los Angeles. And of course there remain in common unquestioning parlance such mystifying names as the Los Angeles Lakers, transplanted from Minnesota, “the “land of 10,000 lakes,” or the Utah Jazz, formerly of New Orleans.

By bumping “Anaheim” to the caboose position of his new name for the team, Moreno has brilliantly anticipated that newspaper and other media practice would inevitably truncate the team's cognomen to “Los Angeles Angels.” In my view this has already happened. Short team nicknames like Yanks or Sox or Cubs or Bums were born a century ago largely of headline writers’ desperation to squeeze character count. Things may not have changed so much today, even given the limitless “real estate” of the web page or the unfettered air space of radio and tv.

The Moreno Stratagem appeared to be something new, not inadvertently redundant, for which I could find neither name nor precedent: the deliberate packing of a term with so much information, even irrelevance, that editors could be counted upon to reach for their blue pencils, and the cutting could be counted upon to come from the rear ... especially because that prepositional phrase “of Anaheim” is a hanging chad, inviting its own snip.

I was frankly flummoxed. I ran through my whole list of rhetorical devices, from alliteration to zeugma, and could find nothing that quite fit the Moreno Stratagem. Oxymoron came close, but a subterranean level of common sense or humor is discernible in “jumbo shrimp” or “adult male” that is not evident in “Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim.” And then I found it: Anesis (an’-E-sis): A figure of addition that occurs when a concluding sentence, clause, or phrase is added to a statement which purposely diminishes the effect of what has been previously stated.

Would a rose by any other name smell as sweet? Does calling some preexisting thing by a new name confer a new reality upon it? Lincoln once was asked, “If we called a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs would a dog have?” His reply:

“Four. Calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it a leg.”

Though still dazed after the annual eating contest that Thanksgiving has become, I kept my eyelids pried open long enough to watch plenty of sports. If you are a New York fan across the four major team sports, this was as exciting a weekend as we’ve had in a long time.

In basketball the Knicks won in overtime on a buzzer-beater by the smallest player on the court, while the Nets won in overtime over the Lakers despite Kobe Bryant’s 46 points. In hockey the Rangers won an overtime shootout that was thrillingly extended to a record fifteen rounds; the Devils and Islanders won weekend games too. The Mets landed free agents first baseman Carlos Delgado and relief pitcher Billy Wagner and now seem plausibly pennant-bound in ’06; the Yankees will close a deal soon and, as always, will assure a way into the playoffs. The Giants rallied in the final minutes to create an overtime scenario, only to kick away three opportunities for a game-winning field goal. Only the Jets lost, but they may be forgiven all in this injury-shattered season, once so rosy.

Jets, Mets, Knicks ... Nets, Devils, Islanders ... Rangers, Giants, Yankees. In a tryptophanic reverie I began to wonder how did New York’s teams come to be known this way? I have written articles previously in this space about why athletes play, why fans root, and how team colors arose. It occured to me that I had created a chair with only three legs, and needed now to talk about how sports teams, mostly in our neighborhood, came by their names. (It would be fun to go far afield to plumb the gunslinger psychology of, say, the Houston Colt .45s, Baltimore Bullets, and St. Louis Bombers, but I have been accorded limited space.)

The oldest of surviving New York sports names is Knickerbocker, attached to the famous baseball club of Alexander Cartwright and his fastidious companions who in 1846 began to play the new game. The Knicks ceased to play competitive baseball in the 1860s and the club disbanded in 1882, but in 1946, a century after they had played the first match game by modern rules, their name was exhumed by a team playing a sport that wasn’t even invented until after the Knicks were gone. Today’s Knicks show no sign of their borrowed heritage in their corporate identity, but their first logo clearly invokes the Old Dutch Patroons of Washington Irving.

Next oldest is — surprise! — the Mets. Their official name of the New York Metropolitan Baseball Club came into being in 1961, the year before they took the field for their inaugural campaign at the old Polo Grounds, haunted with memories of the departed baseball Giants. However, as the Metropolitan Base Ball Club of New York the Mets had provided a major-league entry in 1883-87 and could trace its first incarnation back to 1857. The Jets and Nets were both named to rhyme with Mets, although each was born under another name—the Jets as the Titans (also playing in the Polo Grounds and echoing the Giants), the Nets as the Americans.

Newspapers attached the “Giants” name to the Chicago club also known as the White Stockings (today’s Cubs) in the mid-1880s, but by 1888 it had stuck to New York’s National League entry, which had previously been termed the Gothams, after an amateur club of the Knickerbocker era. When a New York entry came into the National Football League in 1925, it leased the Polo Grounds and took the baseball team’s name. These Giants vacated the Polo Grounds for Yankee Stadium a year before the baseball team hightailed it to San Francisco. Yet even today, local sports announcers call the team “the New York Football Giants,” in apposition to a ghost.

In the early days of major league baseball the press would usually refer to teams by their geographical locators alone: the Bostons would play against the New Yorks, the Detroits against the Chicagos. As some cities acquired additional big league entries, and sports sections began to enlarge, there was a need for short, punchy mascot names: Brown Stockings (“Browns”), Red Stockings (“Reds”), and so on. Brooklyn’s Trolley Dodgers of 1883 (so named because fans crossing from the trolley to the ballpark had to be watchful for cars arriving by intersecting lines) became Superbas and then Dodgers, Robins and, often as not, Bums. The Bums went west to Los Angeles, but when the American Football League began play in 1960, the team placed in L.A. (and long since relocated to San Diego) was called the Chargers because it sort of rhymed with Dodgers.

The Yankees arrived on the scene around 1913, although the team had joined the American League a decade earlier to replace the Orioles of Baltimore. They played as the New Yorks, the Greater New Yorks (referencing the 1898 consolidation of today’s five boroughs into one city), and the Highlanders. This name reflected not only their Hilltop Park in northern Manhattan, overlooking the Hudson River from the site of today’s Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, but also their owner Joseph Gordon. Punning newsmen referenced the Gordon Highlanders, a fabled Scottish fighting regiment.

Actually, the name “Yankees” is more apt for a Boston or New England team, and the NFL fielded a Boston Yankee eleven. If turnabout is fair play, then it is fitting that the home of the Braves (originally in Boston, then in Milwaukee, and since 1966 in Atlanta) derives from New York’s Tammany Hall, whose leader James Gaffney bought the team in 1912.

New York’s first National Hockey League franchise was the Americans, founded in 1925. When boxing promoter and Madison Square Garden president Tex Rickard installed a second team in 1926, fans and sportswriters referred to the new squad as “Tex’s Rangers,” and the name stuck. Staying with hockey for a bit, New Jersey’s Devils were originally the Kansas City Scouts, transplanted to the Pine Barrens and renamed for a Sasquatch-like swamp critter that was said to prowl there. The Islanders name is a prosaic restating of their location on Long Island, while associating with the larger metropolis of New York to which so many Island residents commute for work.

Irksome to me lately has been a baseball attempt to follow in the footsteps of the “Long Island Islanders,” creating a linguistic conundrum with odd resonance. The owner of the team formerly known as the Anaheim Angels (until the 2005 campaign) is Arte Moreno, who has revealed himself to be not only a shrewd businessman but a linguistic strategist of the first order. By renaming his team as the “Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim” he remains in technical, perhaps niggling compliance with the term of his lease with the city stipulating that Anaheim is to be included in the team’s name. By adding “Los Angeles” he intends to surf on the presumed benefits of attaching to a larger metropolitan area, with a presumably more lucrative media profile.

The official team position on the new name is that it honors the team’s roots, for the expansion franchise commenced play in the ballpark of the former Pacific Coast League Los Angeles Angels. But the franchise has been located in Anaheim since 1966. An equivalent “honoring” of a vacated city might be the Brooklyn Dodgers of Los Angeles. And of course there remain in common unquestioning parlance such mystifying names as the Los Angeles Lakers, transplanted from Minnesota, “the “land of 10,000 lakes,” or the Utah Jazz, formerly of New Orleans.

By bumping “Anaheim” to the caboose position of his new name for the team, Moreno has brilliantly anticipated that newspaper and other media practice would inevitably truncate the team's cognomen to “Los Angeles Angels.” In my view this has already happened. Short team nicknames like Yanks or Sox or Cubs or Bums were born a century ago largely of headline writers’ desperation to squeeze character count. Things may not have changed so much today, even given the limitless “real estate” of the web page or the unfettered air space of radio and tv.

The Moreno Stratagem appeared to be something new, not inadvertently redundant, for which I could find neither name nor precedent: the deliberate packing of a term with so much information, even irrelevance, that editors could be counted upon to reach for their blue pencils, and the cutting could be counted upon to come from the rear ... especially because that prepositional phrase “of Anaheim” is a hanging chad, inviting its own snip.

I was frankly flummoxed. I ran through my whole list of rhetorical devices, from alliteration to zeugma, and could find nothing that quite fit the Moreno Stratagem. Oxymoron came close, but a subterranean level of common sense or humor is discernible in “jumbo shrimp” or “adult male” that is not evident in “Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim.” And then I found it: Anesis (an’-E-sis): A figure of addition that occurs when a concluding sentence, clause, or phrase is added to a statement which purposely diminishes the effect of what has been previously stated.

Would a rose by any other name smell as sweet? Does calling some preexisting thing by a new name confer a new reality upon it? Lincoln once was asked, “If we called a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs would a dog have?” His reply:

“Four. Calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it a leg.”

--John Thorn